THE SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM CELEBRATES ITS FIRST 60 YEARS AND THE LONG AWAITED RECOGNATION AS UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE

Text by: Annarosa Laureti

Amongst the squared and sharp-corned shapes of New Yorker buildings of Fifth Avenue, at 1071 a bizarre soft contour sticks out… “Washing machine”, “imitation beehive”, “giant toilet bowl”, the upside down ziggurat of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright gained over the years not so pleasing monikers.

Conceived by the very American architect as a creation that would “make the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the World of Art before”, the manifesto building of the father of the “organic architecture”, last Monday celebrated its first 60 featuring free entries, tours and conversations, jazz sessions, an anniversary party opened to Foundation’s members and lots, lots of delicious cupcakes!

Going beyond the mid-life crisis without hurdles, the “Wright-designed masterpiece continues to serve as a beacon and inspiration for visitors from around the world”, as Richard Armstorng, Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, said

It was October 21st, 1959, when the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation first opened to the public its exhibition space definitely changing the whole concept of the museum.

No longer mere container of art pieces but work of art in itself, the “archeseum” – as named by Wright – soon spread a new way to wholly live the exhibition experience. Absorbed in a “temple of spirit” where radical art and architecture are engaged in a close dialogue with each other, the visitor in fact for the first time let himself driven in the museum’s discovery by the very building’s structure.

According to the architect there was only one rule to follow: stepping on the upward growing spiral ramp from up to downstairs, looking for an artistic purification.

Despite detractors and several criticisms – 21 artists signed a petition against the exhibition of their works inside the museum before the inauguration – the transcendent architecture became an icon and it has also been inscribed last July on the UNESCO World Heritage List as part of “The 20th Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright”, together with other seven major Wright’s works.

More than a simply cold-served revenge (the nomination has been processed for over 15 years), according to Barbara Gordon, executive director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy – an international organization aimed to the preservation of all Wright’s remaining built works – this UNESCO recognition “is a significant way for us to reconfirm how important Frank Lloyd Wright was to the development of the modern architecture around the world”.

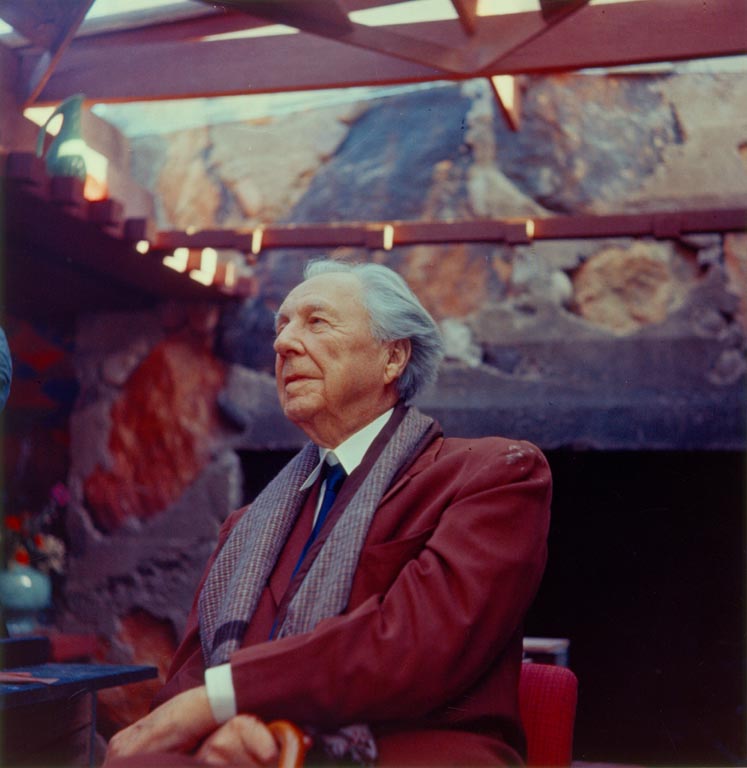

Born in 1867 in Richland Center, Wisconsin, straddling two centuries, Wright began his career joining in 1888 Louis Henry Sullivan’s studio and then the Chicago School movement. Theorizing with his master the concept of the “organic architecture” – whose main purse was that of a perfect integration between nature and dwelling – he applied his knowledge and energies on the design of businessmen’s villas near Chicago.

Renamed “prairie houses” the latter – as the Unity Temple and the Frederick C. Robie House, both on the UNESCO World Heritage List – were the first concrete expression of Wright’s Prairie School architecture style, strictly linked to the Arts and Crafts Society.

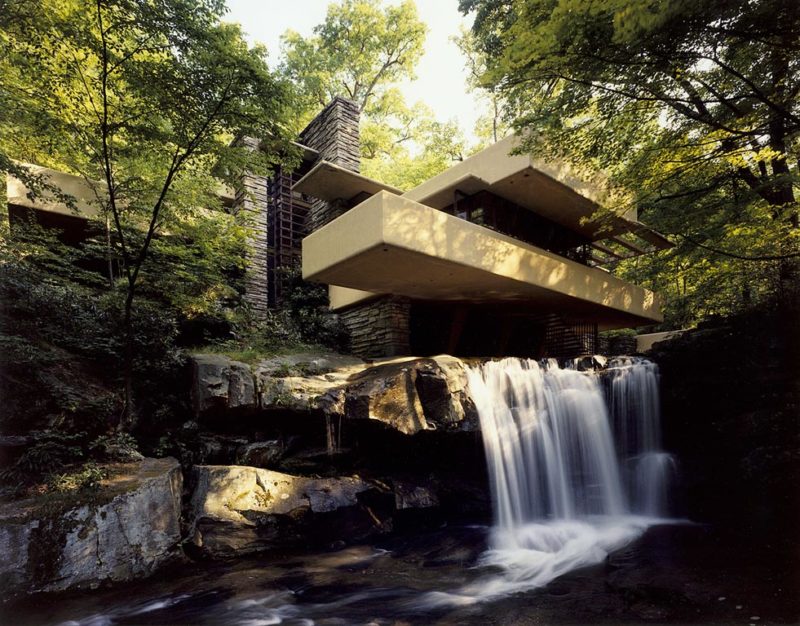

However Wright’s consecration as the main “organic architecture” interpreter – and as one of the main Modern Architecture personalities – came with his “Fallingwater” masterpiece. Recognised by UNESCO as well, the gorgeous Kaufmann’s villa in Pennsylvania, literally constructed on a cascade, was considered as the best actualization of the harmony between natural and human designs.

Always devoted to the principle of a spatial continuity where every single element is conceived as part of the whole – “It is one thing, all an integral, not part upon part. This is the principle I’ve always worked toward” – the American architect designed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum thinking about a living organism. Although he couldn’t see his own creature finished – unfortunately he died just six months before the building’s opening – he passed on in inheritance a modern Babel Tower able from over 60 years to unite people throughout culture and art worlds.

Cover: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Photo: David Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York