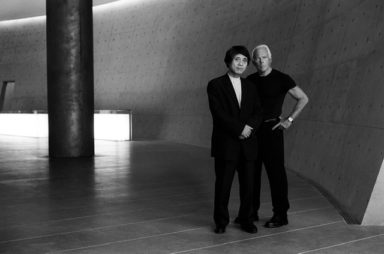

Richard Rogers, the archistar who built the Lloyd’s headquarters, Marseille and Madrid airports, the courts of Bordeaux and Antwerp, the Millennium Dome and, with Renzo Piano, the Beaubourg, has died. Winner of the Pritzker Prize, he altered the skylines of Paris and London with colourful and surprising designs that transformed architecture not only inside but from top to toe

Text by: Domenico Costantini

Richard Rogers has died, after a long convalescence from a bad fall. He was born in Florence in 1933 into a Jewish family, his father a Venetian doctor and his mother a ceramist from Trieste, taking the name of his grandfather Riccardo Geiringer, a Generali executive. The racial laws of 1938 brought the family to London, still dominated by the fumes of coal heating, where the young Rogers had many difficulties growing up in the suburbs due to his limping English and dyslexia. After the war, he was sent for military service to Allied-occupied Trieste, where he was able to re-embrace his maternal relatives. After studying architecture, in which he came into contact with Pop culture (his acid green and shocking pink shirts are legendary), he had a decisive experience in the United States at Yale under the direction of the brutalist-perfectionist Paul Rudolph, but above all he met another English student, the son of Liverpool workers, Norman Foster, and together they travelled around the country to visit famous buildings that would form the basis of their future projects. Together with others, including his first wife Sue Bromwell, they founded Team 4 and for a while designed buildings defined as “high-tech”, a definition he did not like because, he repeated, “Brunelleschi’s dome was also high-tech”. Of course the structure came first, it was never hidden but always extrapolated and exhibited, contrary to what is commonly done. Foster’s differences with him, including political ones, and his concern for environmental issues brought him closer to Renzo Piano, with whom they won the competition for the Beaubourg in 1971, not yet forty years old, and immediately became the bad boys of international architecture for the neo-futurist irreverence of a building-machine planted in the centre of Paris, with the visible systems as brightly coloured as their shirts.

A lifelong Labour leader, he was part of the civil rights movement and post-1968 social struggles, and it was at a demonstration that he met Ruth Elias, an activist and daughter of Jewish immigrants, who became his second wife. He built landmark buildings such as the Lloyd’s headquarters,

the airports of Marseille and Madrid, the courts of Bordeaux and Antwerp, the Millennium Dome, with an associate firm that excelled in internal community rules (the first to give maternity and paternity leave to employees).

In the 1980s and 1990s Rogers’ struggles were spent improving London’s public space, not only with his (won) battle for the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square, but also his (lost) battle for the complete redevelopment of the Thames waterfront. Public space, “A place for all people” as he says in his autobiography (published in Italian by Johan&Levi) has been the leitmotif of his architectural and political commitment.

“Architecture is inseparable from the social and economic values of the individuals who practice it and the society that supports it.” RR