This year’s events (from 22 to 24 September 2017) include an array of exciting new programme elements which are dedicated to new works and young talents. Unseen Amsterdam includes the Fair, CO-OP, the Book Market, the Living Room, Onsite Projects, Exhibition’s, Open Gallery Night, and the Unseen’s City Programme. Here some highlighted suggestions.

Onsite project Para/Site

Gosschalklaan

Westergasterrain

Klönneplein 1

1014 DD Amsterdam

For this interactive project, G/P Gallery (Tokyo, Japan) introduces us to young Japanese artists who use performance as an extension of their photographic practice. These interdisciplinary works push the boundaries of the photographic medium by inviting visitors to experience photography in unexpected hands-on formats. Participating artists include Takaaki Akaishi, Kenta Cobayashi and the artist collective Spew (Daisuke Yokota, Naohiro Utagawa and Koji Kitagawa).

PARA/SITE In conversation with Spew

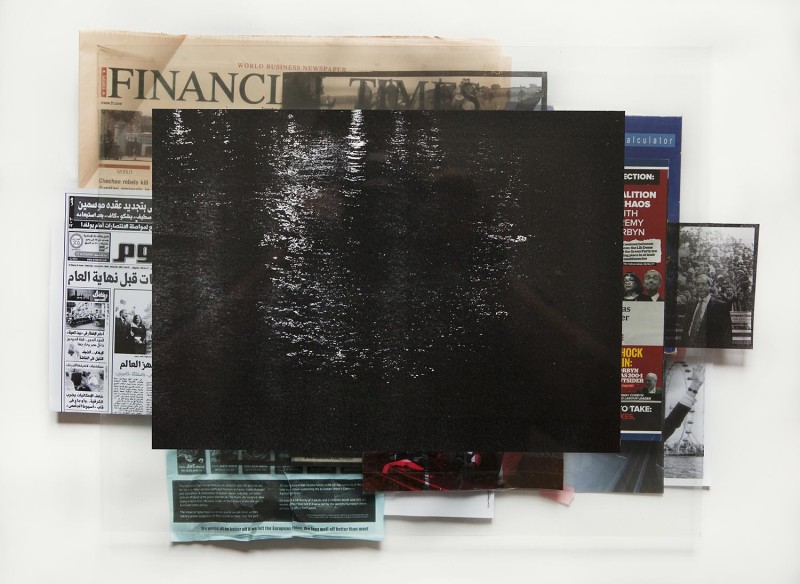

Spew is a Japan-based artist collective comprised of artists Daisuke Yokota, Naohiro Utagawa and Koji Kitagawa. The collective’s ideology is rooted in looking at photography ‘beyond the frame’, and each artist makes a point to actively engage in activities that push the boundaries of the medium. At Unseen Amsterdam 2017, Spew is developing and performing a production for the Onsite Project Para/site, presented by G/P Gallery.

In this feature, we talk to the collective about what inspires their practice, and what compelled them to develop a platform for collaborative projects as opposed to solo work.

When did you first become interested in photography?

Somewhere between 10 and 20 years ago.

Why did you feel the need to form a collective?

With a collective, you can accomplish things you wouldn’t be able to do on your own. It’s similar to going on a vacation alone: it’s nice, but it’s also nice to travel with friends and have fun together.

Your work pushes the limits of photography to new extremes. What do you think the future holds for the photographic medium?

No one can predict the future, but we feel very tied to the now. Modernity was made possible with technology, technical developments and the revival of old school techniques, but we find this all looks boring. We think the things that are not organised or understood are what is important now.

Are there any specific photographers or performance artists from Japan who have influenced your practice?

We have so many influences that it is impossible to name just one.

What comes first – photography or the idea for a performance? How do these play into one another?

We never separate our photography and our performance – they are equal. We first take action, and then we photograph it. The resulting images can act as a record or an art work. When we do something, it can be a play or a performance. It all comes from a simple idea, so we are not trying to break up our work.

What are the main differences between working as a solo artist vs. working with others in a collective?

Solo projects are about organising and presenting a number of your works at the same time. When you work as a group, it is very important to accept confusion and difference. We like to work in a way that focuses on the result, whatever it may be, rather than making a definitive plan before we even start. In this sense, working alone vs. working with others is completely a different practice.

PHOTOBOOK MARKET STATEMENTS

Which is the role of the photobook market today? The project Market? What Market? is kicking off with a series of three entries on Unseen Amsterdam’s website, written by guest contributors Gerry Badger, Olivier Cablat and Sebastian Arthur Hau. Conversations surrounding the issues raised by the authors will continue during the roundtable discussions in Aarhus and Amsterdam, and all content will be made available to download in an online booklet after the main events, including additional unique materials by Natalia Baluta and Carlos Spottorno.

Details for the simultaneous roundtable events are as follows:

Photobook Week Aarhus

Getting It Out There: Publishing and Distributing the Photobook

Fri 22 Sept

11.00-12.00

Unseen Book Market

Making, Sharing, Selling: The Photobook Market Today

Sun 24 Sept

16.00-17.00Details for the simultaneous roundtable events are as follows:

Photobook Week Aarhus

Getting It Out There: Publishing and Distributing the Photobook

Fri 22 Sept

11.00-12.00

Unseen Book Market

Making, Sharing, Selling: The Photobook Market Today

Sun 24 Sept

16.00-17.00

THE PHOTO COLLECTOR BOOK MARKET

Here Gerry Badger* takes the stand and shares his views on the photobook market today.

The idea of a photobook market is quite complex. They have clearly grown in popularity since the photobook became an object of academic study, but I am unsure exactly how much this recognition has increased. There is a lot of talk about photobooks, and hordes of people look at them at festivals, but I don’t know how much of this is translated into sales. There are a lot of books chasing a certain level of spending power in a world where spending power has eroded with time.

A market for collectors?

It seems to me that there are two – possibly three – markets for photographic books. Firstly, there is the antiquarian market, where high prices are paid for classics in the genre. However, it should be noted that this is very much a ‘condition market’, which has begun to deflate in recent years. This market is obviously for collectors, whose aims are not just the establishment of pride for owning something most people don’t, but who regard the photobook as an asset – something that increases in value, incorporated into a pension plan. I remember one collector of photobook classics saying, “It’s nice to look at my shelves and know they’re making money”.

Contemporary photobooks as investment?

Some of these criteria spill into the second photobook market: contemporary photobooks. These include books that determine the buzz and debate around contemporary photography. Those who can’t afford the classics are able to pick out future classics, and can thereby make a prospective profit. Of course, many collectors buy them for the love of photobooks and photography, but the feeding frenzy generated by certain books, and the insistence on having signed copies, suggests that the investment impulse is still very much at work.

Photographic books or photobooks?

There is a third market that tends to be overlooked, which is the market for photographic books rather than photobooks. These photographic books include retrospective monographs, exhibition catalogues, historical studies, and so on. If you are interested in photography as opposed to interesting objects, the photographic book market is important. It is also less likely to attract the investor or collector, although as soon as any book goes out of print it demands a premium.

Festivals for photobooks…

One thing is clear: the number of available photobooks has grown to a point where no one can completely keep up with them. This makes festivals a vital component of the market. I don’t know exactly how many books are sold at these events, but festivals are certainly the best place to see the latest photobooks. It is also a place where we get seduced into unwise purchases – those books you look at once and once only, the flaky books about which the wise John Gossage once observed, “are all icing and no cake.”

————

*Gerry Badger is a British photographer, architect and photography critic. He has published a number of books, including Collecting Photography (2002), The Genius of Photography (2007) and The Pleasures of Good Photographs (2010), for which he received the Infinity Writer’s Award by the International Center of Photography (NewYork) in 2011. Additionally, he co-wrote the essential series and the reference book in the field of the photobook with Martin Parr, titled The Photobook: A History (London: Phaidon Press, 3 volumes, 2004, 2006 and 2014).

The DIY Photobook

Here Olivier Cablat* takes the stand and shares his views on the evolution of the photobook in the digital realm.

The term ‘photobook’ was never used prior to the year 2000. This is an observation that David Campany wrote in 2012 in his essay The “Photobook”: What’s in a name? In 2004, Martin Parr and Gerry Badger co-edited the first volume of The Photobook, A History, an anthology of books from the 20th century that all represent the emergence of publications containing printed photography in the field of Art History. The Photobook, A History is quite different from other anthologies of the same kind, in the sense that it was created by main players in the field: photographers, authors of several theoretical and photographic books, and prominent photobook collectors. Traditionally, recorded history is realised by an historian, just as a photobook is supposed to be published by a publisher. But in recent years, the roles attributed to professionals in the realm of photobooks have started to change.

Indicated by the 3 letters D-I-Y, Do It Yourself refers to the possibility of breaking the professional mould, encouraged by online blogs and new digital techniques. A few decades ago, a photobook collection like Martin Parr’s was only made possible through years of travelling, sifting through hundreds of libraries and flea markets. Now, with platforms like Ebay, products from all over the world are accessible in a few seconds. The 21st century bookmaker can consult blogs, online bookshops, tutorials and forum discussions. They can design their books with software, send a layout by e-mail, understand screen colour proofing, present it on social networks, and announce and distribute it on their personal website.

A new wave of self-publishing

All the factors that have contributed to this new wave of self-publishing come from countries all over the world. Traditional codes were broken, reappropriated and re-used in books of all sizes and formats. This explosion of different publishing practices operates in several realms, such as self-published books, micro-editions, or books by smaller publishers experimenting with news ways of conceiving, producing and distributing publications. The digital space has not only strengthened the growing interest in this traditional and polymorphic object – it has also assisted several generations of artists with breaking down the limitations of their reach.

I am one of these artists.

When I was ready to publish my first photobook in 2009, I didn’t think any editor was ready to invest in an unknown 30 year-old photographer experimenting with documentary and found pictures. But I was also convinced that if I wasn’t happy with how things were done, I would just have to invent a way to do it myself. I made my first photobook Galaxie (White Press) using a printing technology called Print On Demand (POD), with allowed my team to digitally print a small quantity of books and repeat the process bit by bit. Each book was more expensive compared to purchasing one in an edition of a few thousand made all at once, but we were able to make the edition possible with a reasonable investment and without the help of any institutions.

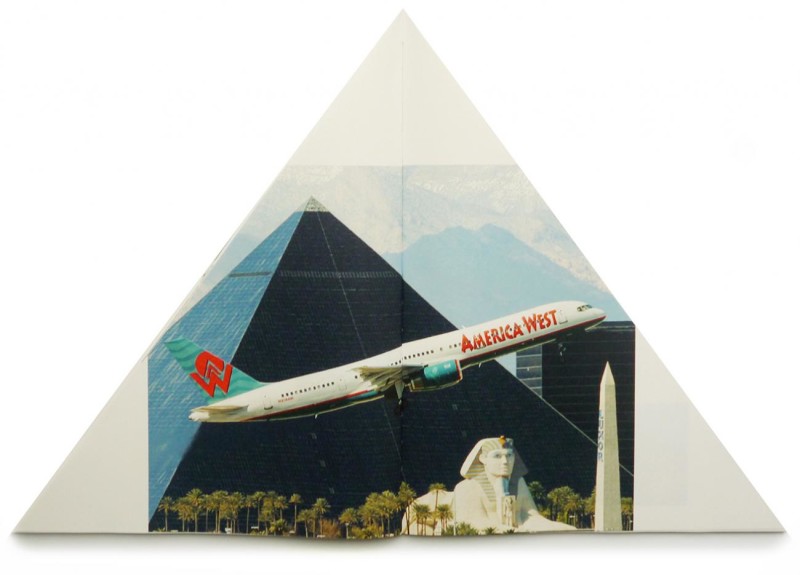

The photo book as a preferred art form

The photobook then became my preferred art form, and each one of the books I create supports aspecific relation with the digital. Enter The Pyramid (RVB Books, 2012) was created using found images from the internet; Fouilles (Filigranes, 2013) was made by mixing different kinds of images, such as animated gifs and Google street view captures with my own pictures. DUCK, A theory of Evolution (RVB Books, 2014) extended the reading experience into augmented reality 3D content.

As for many artists from my generation, the digital helped me become published, and assisted my experimentation with an art form that was previously reserved for a small number of artists. The software facilitated an understanding of different types of professions, new printing processes permitted the production of a small quantity of books within a reasonable budget, and the Internet gave me the opportunity to access knowledge that would take several lifetimes to research in the analogue world.

——-

*Olivier Cablat is an artist, photographer, teacher and Artistic Director of Cosmos Arles Books with Sebastian Hau. He published 12 photobooks between 2009 and 2017 with publishers White Press, Filigranes, RVB Books, and as a self-publisher. Since 2015, he has been pursuing a practical and theoretical doctorate titled “Digital and Photobooks” at the Scientific and Arts Laboratory at Aix-Marseille University.

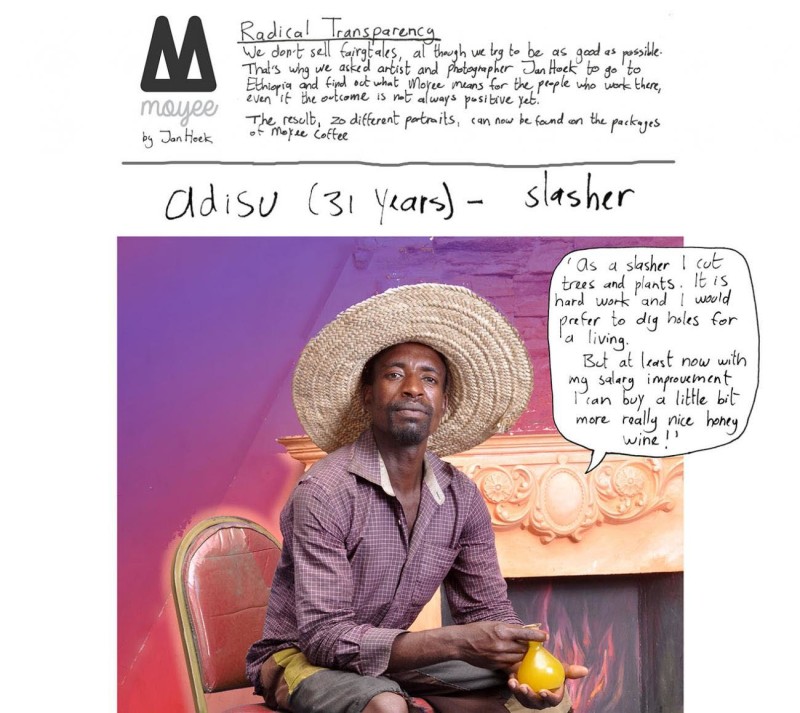

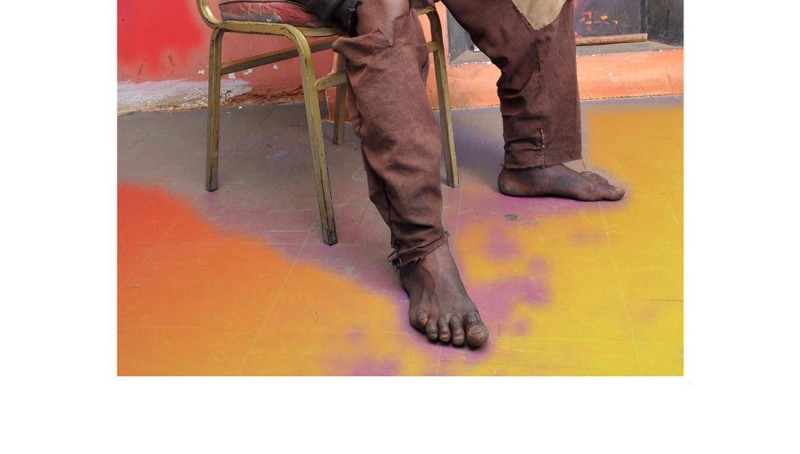

Moyee Coffee at Unseen

Throughout a range of industries, sustainable business models are increasingly becoming a necessary standard, and many companies are employing artists to assist in spreading awareness about their causes through visual storytelling. Photographers and other image makers are commissioned to create original content that acts as an extension of their own artistic practice while simultaneously bringing light to issues in contemporary business and their relevant communities. One such company is FairChain coffee brand Moyee Coffee, who is a partner at this year’s Unseen Amsterdam, serving fresh coffee on site and out of their own coffee truck located on the grounds. In the spring of 2016 Moyee partnered with photographer Jan Hoek, who travelled to Ethiopia to create the Faces of FairChain campaign, resulting in a series of playful images grounded in thephotographer’s amusing stylings. Though humorous, the images present a critical analysis of FairChain’s mandate to improve the lives of their employees in a series of theatrical portraits coupled with quotes that address the economic trade-offs that result from establishing a FairChain brand. The campaign is an impressive reminder of the importance of transparency in the corporate realm, revealing how artists are best suited to take on the role of navigator on the road to corporate responsibility. Unseen is delighted about the continued partnership with Moyee, whose dedication to emerging artists reflects our own mandate.

Jan Hoek has presented his work at Unseen Amsterdam at our previous instalments, and is also a member of this year’s participating collective Charles Goes to Arles.

Photo: © Jan Hoek