ON THE EVE OF THE MET MUsEUM’S EXHIBITION ON CAMP WE TaLKED WITH ICONIC QUEeR FILMMAKER AND WRITER BRuCE LABRUCE ON CAmP IN 2019 AND THE DIGITaL AGE

You can read the whole interview in Collectible DRY 11, in newsstands now, what follows is just a short edited version.

Text by: Riccardo Slavik

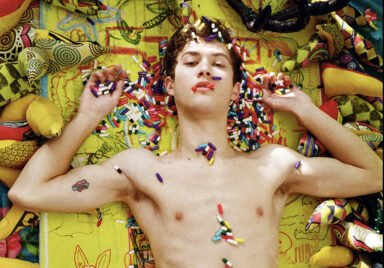

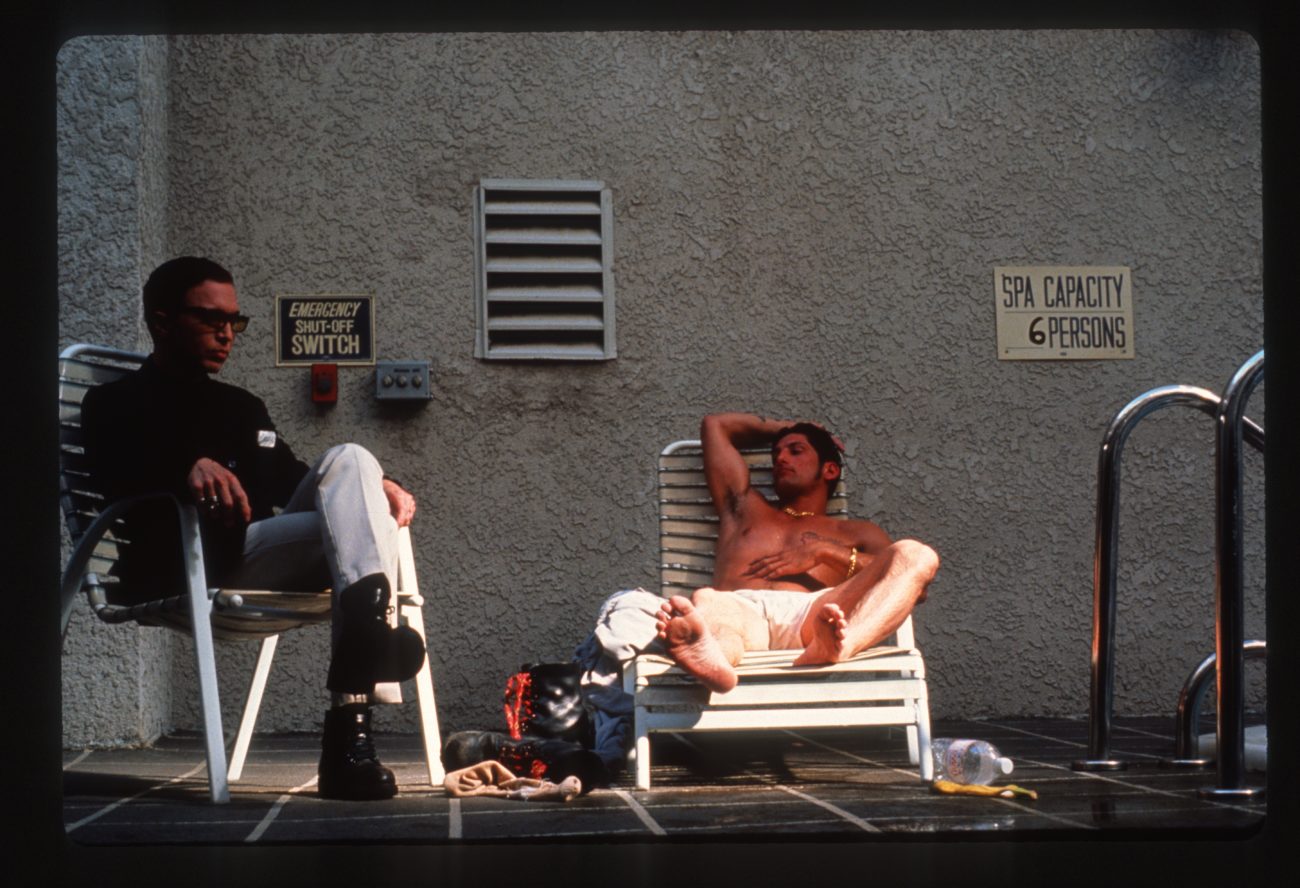

Images by: Bruce LaBruce

Bruce LaBruce is an internationally acclaimed filmmaker and artist. At the forefront of the Queercore movement in the mid-1980s, he has helped shape Queer Cinema through iconic and pivotal works such as No Skin Off My Ass, Hustler White and The Raspberry Reich. Although especially well known as a director, he is also a very prolific visual artist and writer. His ‘’manifesto’’ Notes On Camp/ Anti-Camp (first presented at the Hau Theater in Berlin in March 2012 ) is an important, though not overtly serious, queer critique of Susan Sontag’s Notes On Camp, and when the Metropolitan Museum announced its big May 2019 fashion exhibition ( which famously starts the day after its now globally followed Met Gala) would be: Camp: Notes On Fashion, I thought it would be the perfect excuse to ask him a few things about the state of Camp in our fast, connected, pervasively ironic world.

DRY: In Notes On Camp /Anti-Camp you wrote: “Sontag identifies camp as “a sensibility that converts the serious into the frivolous” (rendering her article another kind of betrayal by taking camp far too seriously), and as a matter of “taste” that “governs every free (as opposed to rote) human response.” Camp, then, is also an existential condition as much as a sensibility: an enormously serious and profound frivolity.’’ It seems to me that defining Camp and divulging it is, in a way, a betrayal of it. Do you think that the Met dedicating an entire exhibition to it could be the ultimate betrayal? The final nail in its coffin?

BLB: The Met Gala already used the theme of camp last year with Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. You can’t get any campier than the Catholic church! ( Although few stars or their stylists seemed to grasp the inherent political nature of Camp, which could have been easily articulated through the use of lesbian nuns, gay priests, or altar boys in an ironically eroticized context.) Fellini realized this campfest far more profoundly in his film Roma with his infamous “Vatican Fashion Show”, in which gay priests roller-skate hand in hand, and abstract, high-collared Cardinal vestments are pimped out as extrapolations of the disco ball, mixing gay signification with the ultimate expression of artifice and the carnivalesque. (I have to point out one exception, which was superdyke Lena Waithe’s rainbow flag cape, designed by Carolina Herrera, worn over a resolutely male black suit, which nailed the political and playful queer spirit of camp, an example of good queer/lesbian camp.)The Met Gala is already itself a camp event, so taking on “Camp” as its theme is resoundingly redundant. It amounts to a co-option of camp, emptying it of its queer political significance in the service of the promotion of vapid celebrity and late capitalist excess and decadence. And despite all the gay designers and stylists behind the scenes, it remains remarkably heteronormative. In this sense, it is a betrayal of camp.

DRY: Do you think, being the Met exhibition primarily about Fashion, that it might run the risk on focusing mainly on Irony, which is but one of the many aspects of Camp?

Andrew Bolton, curator of the exhibition was quoted in Vogue as considering one key aspect of Camp the idea of “failed seriousness—not consciously trying to be Camp ”, which I think borders on confusing Kitsch and Camp, as Philip Core defined it, Camp is ‘The Lie That Tells The Truth’’ an exaggerated frivolity that hides seriousness from the eyes of the mainstream, which makes me wonder about the essential premise of the exhibition itself…

BLB: I take issue with the notion that camp is “failed seriousness.” Camp is very serious, although it may deliberately disguise itself as the non-serious. For example, when I initially delivered my paper Notes on Camp/Anti-Camp at the Camp/Anti-Camp conference in Berlin in 2012, I presented it as a camp performance which I took very seriously, but then again, not seriously at all, mimicking the approach that Sontag took in her article. So I used signifiers of the high-serious institutional, academic lecture – a blackboard, scientific-looking charts, etc. – for ironic effect, although my thesis about non-seriousness was quite serious – identifying (corrupted) camp as the new default sensibility of the world, a mindless, humourless, and pointless theatricality and artificiality that has dethroned irony. (One could imagine a scenario in the near future, when camp is exhausted and totally co-opted, where Sincerity becomes the default sensibility, and then Goddess save us all!) Ironically, the piece I wrote was not really meant to be taken seriously as an academic paper, and yet it ended up being published online on academic websites, and it was quoted widely in academic theses. So this is an example of the complexity and the deceptive nature of camp. But today camp has become malignant and sinister. The queer political intervention of camp has been replaced by a conventional, apolitical posture of excess for its own sake, bad taste without irony, and sexual provocations that are decidely unsexy. Despite the hint of apocalypse in the air, the world at the present moment is the quintessence of frivolity, but without a trace of genuine humour or irony. What the Met Museum fails to take into consideration is that the whole goddamn world is camp now, as I articulated in my paper, so naming camp as its theme is somewhat naive and reductive. The Met Gala is already (failed) camp, celebrity itself is now completely bad camp, New York is pretty much camp, and indeed even the President of the United States is pure high conservative camp. The only thing that isn’t camp these days is the fashion world, which has become more aligned with kitsch. It’s mostly garish and tacky (with notable exceptions), and so mindlessly hyper-referential that it’s totally incoherent, which is fine, I guess, if that’s your thing. But what it really amounts to is an over-determined, hyper-referential swamp of empty signifiers, a mindless hodge-podge of signs bereft of meaning.

DRY: On the subject of seriousness and Camp, Christopher Isherwood wrote that you “can’t camp about something you don’t take seriously” which is a concept Scott Long expounded on in The Loneliness of Camp: ‘’ Camp plays with notions of seriousness and absurdity not to deny them but to redefine them […]. Its particular endeavor is to fix the nature of the absurd: the society that laughs at the wrong things has gone wrong. To perceive the absurd is to realize that two conjoined ideas do not belong together. Behind camp is the expectation that, once the absurd is properly recognized, a sense of the serious will follow. ‘’ Do you think Camp runs the risk of being taken too seriously once it becomes part of an academic discussion (I guess this question might be Camp in itself as it quotes academic writings…)? And, given how steeped in the absurd our society currently is, can Camp still perform its role in exposing it?

BLB: I think I’ve already addressed some of the problems of the academic co-optation of camp. In my “essay” I addressed how Susan Sontag’s famous essay is a kind of betrayal of camp because it takes the subject far too seriously, but then again, not seriously at all. (Her assertion that camp is “apolitical” is an insult to every fairy or bull-dagger that ever used camp as a method of survival and coded communication during the pre-liberation and liberation eras. She also failed to grasp the class-consciousness inherent in old school camp.) But the line that jumps out at me is “the society that laughs at the wrong things has gone wrong,” as well as the notion that absurdity (or paradox or sarcasm) can act as antidotes to this confusion because they articulate oppositional ideas that must be understood in order to “get the joke.” (That line reminds me of Gudrun Ensslin’s famous line, which became a credo of the RAF: “There’s no point in trying to explain the right things to the wrong people.”) When irony became the ideological white noise of the nineties, people were routinely saying the exact opposite of what they meant or authentically believed for ironic effect. But it became problematic when people actually lost track of what they believed in the first place, and they started to take seriously the ironic postures they were adopting. (This laid the groundwork for the ascent of Trump, who is able to endlessly contradict himself and tell obvious lies with impunity.) Suddenly, nothing was absurd because everything was true. This ushered in the new regime of camp without irony becoming the default sensibility. To be generous, it could be taken as a kind of Nietzschean “Nothing is true; everything is permitted” philosophy, except that it is less a conscious strategy or ontological position, and more a confusion and cynicism that allows everything to be co-opted by a late capitalist model that has no sense of aesthetics or political consciousness.

DRY: Robert Mazzocco wrote in The New York Review of Books (1966): “A person camps, a person becomes ‘beyond belief,’ when the everyday experience is no longer ‘to be believed.’” Can the worldwide attempt by right wing politicians and organizations to curb and erase the long fought-for rights of queer people and other minorities be the fire that lights up a true resurgence of Camp?

BLB: No. Quite the contrary. The majority of Camp is now the enemy. The phrase “when the everyday experience is no longer ‘to be believed’” is a pretty precise description of the the dominant order of today. Trump, as the most obvious example, has unleashed the Pandora’s box of encouraging people not to trust the very evidence of their own eyes and ears. He is the ultimate expression of the co-optation of the Camp sensibility, expertly wielding its poitical incorrectness, from his deceitful hair to his Stepford Wife to his Medieval Wall to his musty faux-Spanish Mar-a-Lago to his ridiculously long tie to his Pocahontas taunts. Trump uses both Punk and Camp strategies to permanently destabilize the world. I’m not convinced that a resurgence of those same assimilated strategies can now be effective.

DRY: In Camp/Anti-Camp you wrote ‘’What is Bad Straight Camp? Examples would include the exaggerated and stylized streetwalker/stripper style co-opted by many contemporary pop music celebrities, from Rihanna to Britney and Christina on down, a performative femininity by females filtered through drag queens that has transmogrified into an arguably more “avant-garde” style (Lady Gaga, Nikki Minaj) characterized by hyper-referentiality, extreme hyperbole, a crudely obvious, unnuanced female sexuality, and even a vaguely pornographic sensibility which, unhappily, is post-feminist to the point of misogyny: a capitulation to the male gaze and classic tropes of objectification…’’ this was in 2012, is this now too absorbed into the mainstream to be considered Camp? Or can we say that kind of ‘look’ has become just boring nowadays? I think the only artist who can still work that look/attitude with a degree of success is Brooke Candy, because she seems to live it in a much more personal and gender-progressive way, would you still keep that as an example of Bad Straight Camp?

BLB: I think we can safely say that this “look” is now a bit basic and played out, or even square, particularly in the context of fashion and celebrity. As I said earlier, when everything is extreme and over-the-top, it turns into nothing more than an over-determined field of bombastic and meretricious imagery. Someone like Brooke Candy, akin to a lot of the extreme male drag queens, is perhaps more imaginative and futuristic, also incorporating horror and science fiction tropes, as well as baroque and ostentatious historical, cultural and religious references. The extreme gender and non-binary imagery is more interesting, but sometimes I have to wonder if it’s just another fad, like the hula hoop.

DRY: Many have given up on Camp, left it for dead, because our age is steeped in nostalgia and irony, which are core elements of Camp, we are surrounded by pastiches, references and #throwbacks. Even a movie like The Shape Of Water, which could have been such a Camp masterpiece, felt to me like a pointless ( and expensive) exercise in style. Do you think popular culture has produced anything truly Camp in the last few years? What would be your lists of Good Camp and Bad Camp if you had to update your 2012 ones?

BLB: The Shape of Water is the ultimate example of Bad Straight Camp, even though it’s exceedingly gay. It has all the elements of camp – the B-movie Creature from the Black Lagoon sci-fi narrative, the theatrical queen character, the over-the-top Broadway dance sequence, the stereotypical characters such as The Snidely Whiplash Villain and The Dignified Black Cleaning Woman – but again it’s all way too earnest and obvious and irony-free, and, especially, politically correct. (The cliche of the queenie gay show-tune character who falls hopelessly in love with a fascist could have been cheeky and campy, but it just comes across as pathetic and PC.) Even the gender-bending aspect of the creature is biologically-determined, and therefore somehow conventional.

As I’ve already argued, everything is Camp now, which has made the notion of Camp redundant. But there still are examples of Good Camp that occasionally shine through: Cardi B (good straight camp), Peter Strickland movies (good queer camp), “Mandy” (good straight camp), “Vox Lux” (good queer camp), Kenneth Anger Lucifer jackets (good gay camp), Cupcakke (good straight camp), Guy Maddin’s “The Green Fog” (good straight camp), Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, especially the film-within-the-film (genius straight camp)*, and Camille Paglia (good lesbian camp). And there are still plenty of examples of Bad Camp: Bird Box (extremely bad straight camp), Lady Gaga’s A Star is Born (bad straight camp), Melania Trump’s Pith Helmet (bad conservative straight camp), Melania Trump’s “I Really Don’t Care, Do You?” Zara jacket (extremely clueless bad straight conservative camp), Melania Trump in general (bad conservative straight camp), Stormy Daniels (bad liberal straight camp), BlacKkKlansman (bad liberal straight camp), Kanye West’s Roblox and Perrier costumes (bad straight camp), Jeanine Pirro (over-the-top bad conservative straight camp), Kanye West in general (bad conservative straight camp), Jordan Peterson’s bedroom and Jordan Peterson in general (bad straight conservative academic camp), Milo Yiannopoulos (bad conservative gay camp), Elon Musk (bad straight billionaire camp), Kevin Spacey’s “Let Me Be Frank” YouTube video (bad desperate gay camp), Post Malone (bad straight camp), Russia (bad quasi-Communist straight conservative camp), Canada (bad Liberal camp), and many more. Corporate Hip Hop is basically all Straight Camp now, some good, but mostly bad.

* Best line about Camp in 2019, as heard in They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, the documentary about the making of Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, when Orson Welles, directing John Huston, commands, “A little campier still, but masculine.”