Text by: Riccardo Slavik

‘Subcultures represent noise (as opposed to sound): interference in the orderly sequence which leads from real events and phenomena to their representation in the media. We should therefore not underestimate the signifying power of the spectacular subculture not only as a metaphor for potential anarchy ‘out there’ but as an actual mechanism of semantic disorder: a kind of temporary blockage in the system of representation’ Dick Hebdige: Subculture: The Meaning of Style.

Since the birth of ‘the teenager’ (intended as a cultural and economic force) the adolescent desire to both rebel against parents and find solace in the company of kindred souls, Subcultures have created a way for outsiders to somehow fit in and yet spectacularly stand out, to rebel to the mainstream by creating a smaller ‘counter-society’ with its own artifacts, behaviors, norms and values. Each ‘spectacular subculture’ has been characterized by its own fashion, music, slang; these were usually central in creating an identity in and outside the Subculture. For skinheads, for example boots, braces and cropped hair were considered appropriate and meaningful because they represented ‘hardness, masculinity and ‘working-classiness’’, values that were at the core of the skinhead subculture. Subcultural styles therefore followed strict rules to differentiate themselves from mainstream fashion and other subcultures. Even the anarchist, chaos-loving punks differentiated between ‘real’ punks and ‘poseurs’. Authenticity and being part of a group played a strong part in the mechanics of subcultures.

In Subcultures: Cultural Histories and Social Practice, Ken Gelder proposed six key ways in which subcultures can be identified through their:

1 often negative relations to work (as ‘idle’, ‘parasitic’, at play or at leisure, etc.);

2 negative or ambivalent relation to class (since subcultures are not ‘class-conscious’ and don’t conform to traditional class definitions);

3 association with territory (the ‘street’, the ‘hood’, the club, etc.), rather than property;

4 movement out of the home and into non-domestic forms of belonging (i.e. social groups other than the family);

5 stylistic ties to excess and exaggeration (with some exceptions);

6 refusal of the banalities of ordinary life and massification

The advent of internet, fast connections and social media has changed many of the systemic societal ties and mechanisms on which subcultures were based, removing at once spatial and physical limitations and relationships.

‘Kids today — the new generation — they think in different ways. They don’t even have the knowledge of what a subculture is. It is not relevant to them. If they want to wear a punk shirt, that doesn’t mean that they have to listen to punk music or have a political point of view. They don’t have that mentality. In my generation, when we were grunge, we were grunge. It was a mindset.’ Lotta Volkova in 032c Magazine.

This separation between the object and its original meaning, the reduction of the subculture to an image, an ‘aesthetic’ devoid of deeper sense or social ramifications, is directly linked to the rise of social media and a much more visual way of communicating. As people create sub-communities online and find ‘kindred souls’ in places that more often than not have no physical correspondent, as the virtual takes over our ever faster, fluid society, the meaning of subcultures as an aggregative and distinctive force crumbles ever more. Subcultures in the new millennium have become more akin to ‘urban tribes’, though increasingly virtual ones.

This sociological shift has had various ramifications: for one, lacking for most part an actual ‘posse’ or ‘clique’,an IRL actual group of people aggregating in a physical space, post-subcultural ‘tribes’ need to draw validation on other levels, mainly online and through social platforms ( through likes, followers, comments and various other virtual interactions), secondly, the constant ‘bricolage’ of visual elements which comes so naturally to the new generations, who have not experienced the sense of authenticity and belonging that was vital to previous subcultural styles, creates a constant risk of backlash from those who feel to be ‘rightful heirs’ to some degree of authenticity related to any given subculture ( or culture).

When everybody is a ‘poseur’ nobody can be truly ‘authentic’ anymore. Once the many-leveled elements of an actual Subculture are turned into separate aspects (aesthetic, musical, linguistic, etc.) without the social and cultural elements that pulled them together we are left with empty shells that can be played with as one sees fit. Why shouldn’t one use elements of skateboard culture, for example, which has in turn cannibalized surf, heavy metal, punk and other subcultures? It makes no sense to own a skateboard unless one plans to use it, but does ownership and use of the skate itself turn the model who skates to castings into a ‘skateboarder’? Is the act of skating enough to claim the right to be a part of the ‘skate’ subculture? Who keeps tabs on what is ‘authentic’? If the semiotic elements that once posed a threat as the ‘noise’ that opposed itself to the calming sound of mainstream society are stripped of their subcultural and subversive values what do they become? The great power of subcultures was that of investing objects, music, behaviors, with talismanic powers, the magical powers to simultaneously separate and aggregate; taking away the elements that kept the subculture alive, those things can only revert to their original meanings, or lack thereof.

In the post-subcultural state of a society in constant flux identities become nebulous and flexible, visual elements are parts of an image, an aesthetic, created through building blocks which lose their original meanings and retain only a vague stylistic allure.

The classic distinctions of high-school life, the jock, the nerd, the outsider, the punk, the goth et cetera, keep blurring as high fashion adopts and adapts sportswear and subcultural styles, thus changing the nature of one of subculture’s tenets; the very idea of ‘authenticity ‘being put to the test by the fast evolution of style in the internet era.

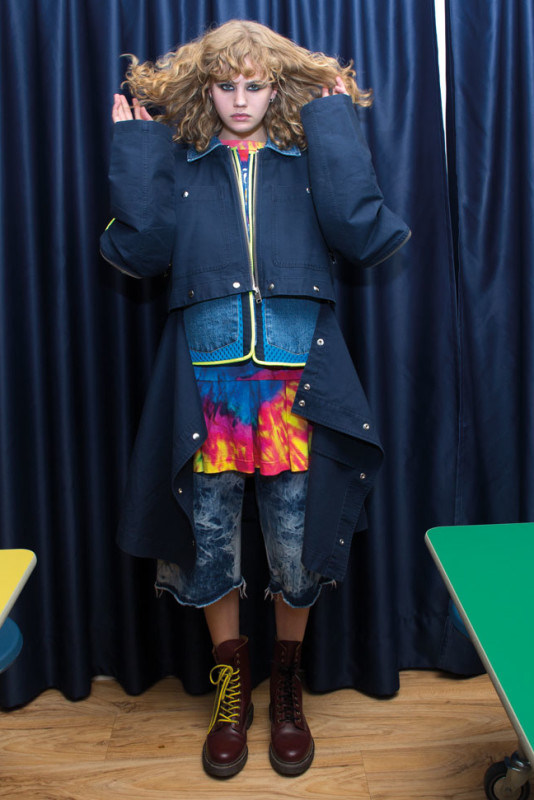

Photography: Lorenzo Marcucci

Styling: Riccardo Slavik

Photographer’s assistant Francesco Anglani. Stylist’s assistant Marco Fusari Imperatore. Make up Grazia Riverditi @Glow Artists. Hair Elisa Rampi. Models: Anna Liisa @Monster Management, Edouard Saussac @Wonderwall, Armand Putza @Elitemodels.

Special thanks to the American School Milan (ASM), Noversaco di Opera (MI), for the location and kindness.