Patti Smith, sheer witness to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s cross-cultural influence on music, headlined the Stresa Festival within a Pasolinian setting, the Tecnoparco, by Aldo Rossi. Herno sponsored the initiative to commemorate the centenary of the great intellectual’s birth

Words DOMENICO COSTANTINI

A craving to live and the downturns of living. An ever soaring “joie de vivre.” These are the sentimental and experiential touchstones where Patti Smith’s poetry focuses. Rock’n’roll, punk and blues poetry, so they say, are part of the lady originally from Chicago who in the streets, hotel corridors and clubs of New York has become the emblem of those who create by indulging their spirituality, respect for the environment and the daily struggles between social classes,proletarian anthems and government power.

The militant verb was once again the focus of his concert, aesthetically, as much as symbolically, the location of the Stresa Festival depicted a scene as if taken from “Scritti Corsari,” the Technopark. Designed in the early 1990s by architect Aldo Rossi and his latest work, the priestess moves between unforgettable hits and more surprising songs – ” Dancing Barefoot”; ” Redondo Beach”; “People Have the Power”, “Because the Night”- navigating through poetry, interpreting some Bob Dylan pieces and dedicating two interludes to the verses of Allen Ginsberg, 25 years after his death, and Leopardi’s “The Infinite.”

On stage, one could find a tight-knit minimalist band, consisting of her son Jackson Smith on guitar, her close collaborator Tony Shanahan on bass and British drummer Seb Rochford.

And it is precisely to the literary but also musical legacy inspired by Pier Paolo Pasolini that Smith has dedicated her concerts: thus, celebrating the centenary of the intellectual’s birth in the style that most characterizes her. She has always been a collector and personal interpreter of the teachings provided by the writer.

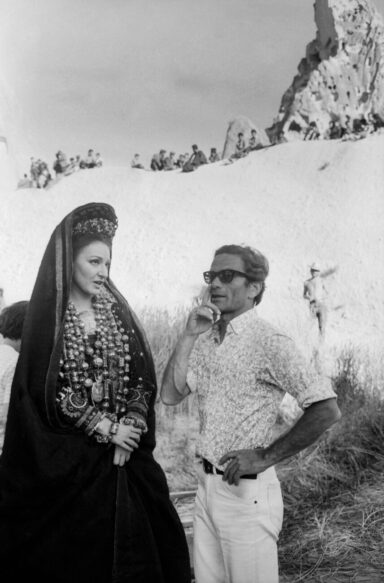

Therefore, we can say that meetings are occasions. To decide whether or not to open the doors of one’s consciousness—in order to let in what sits on the other side—is to take responsibility for non-expectation: what comes comes, for better or for worse. Patti Smith was probably thinking of nothing in particular when she stepped in front of the screen of “The Gospel According to St Matthew”, a film directed in 1964 by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Yet, it was at that very moment that the encounter occurred between her, who was not yet the priestess of rock, and him, who was already the great intellectual who had entered history.

“His film struck me in the late 1960s, that then I began to read books and articles, fascinated by this figure capable of being a poet, director, writer, actor, intellectual, political analyst, all at the same time.”

“The Gospel According to Matthew changed my perception of Jesus,” says Patti Smith, “at a time when I had decided to rebel against religion in order to affirm my identity, Pasolini showed me Jesus from another point of view, pointing me to a revolutionary who was trying to change things. The encounter, the spark, the opportunity to enter a new world, to get to know it and, finally, to celebrate it. In that same year, 1975, he recorded Horses, a milestone in rock history, a convulsive, original album so original and authentic that it is terribly relevant even today and which begins with Gloria’s stinging words “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine.” “In general one must always have the courage to decide for oneself. That is the meaning of that verse from Gloria. It is not a sentence against Jesus or against a religion,” Smith admits, “the meaning is something else, which is that I take responsibility for my actions.” A thought that echoes Pasolinian emancipation, albeit the different nuances, which put both of them on a caravan of time destined to make their ideas everlasting.