“ONE-DIMENSIONAL MAN IS CONDEMNED IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY TO BE SUCCESSFUL OR CRUSHED”

The concept of happiness in a time of crisis like the one we’ve been experiencing since the outbreak of Coronavirus is something that sounds like a chimera. As our daily lives are placed in standby within the walls of our homes, it seems we are asked to set the search of our happiness aside too.

Is it really so? Or, instead, should we take this time of lockdown to reconsider our whole concept of happiness?

Scholars say that we as Western people are less likely to be happy, and this is because we’ve built the idea of wellbeing on consumeristic principles, which applies to instant, instead of long term, gratification. Our big mistake in the reaching of true happiness – what Greeks called “Eudamonìa” and Romans “Vita Beata” – is that we have increasingly misunderstood it with narcissism and relentless ambition.

We incessantly try to accomplish social requirements, by attending high-ranking schools, achieving master degrees, earning a lot of money, settling down and owning a beautiful house, possibly everything before 35. But do all of this actually make us happy? It’s incredibly hard to discern what we really want from what we think we have to do according to external expectations. We may be happy people, happy artists or farmers, happy yoga teachers, writers, entrepreneurs, or happy housewives/househusbands… but most of the time we end up being semi- or even un-happy perpetual chaser for more and more. And you know what? It results that the more you have the less you are happy…

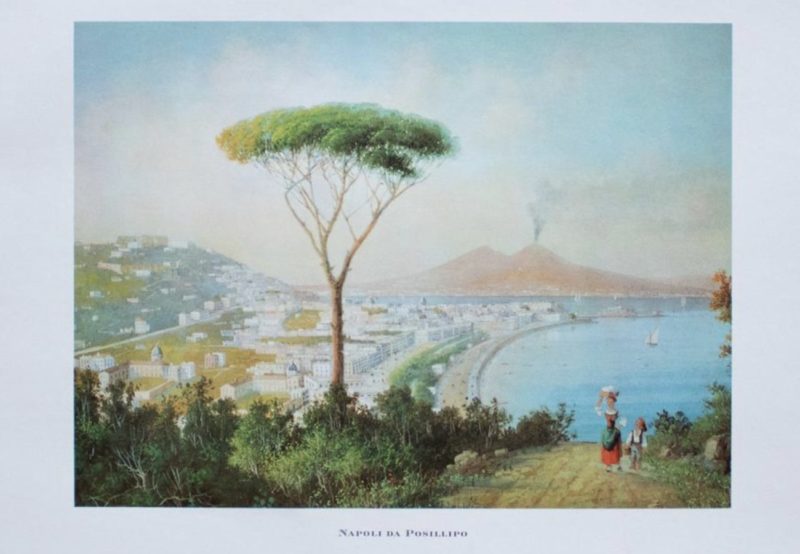

So today we want to share with you the article by the Philosophy professor Sandro Mancini, published on DRY Issue #1. If you are dreaming of a special journey in the Covid-19 aftermath, I’m sure that after reading it, Posillipo, in Naples, will be your first choice. Why? Because we no need a leading position or a profitable career, nor tons of clothes we will hate next year, nor another sunset view to take a nice picture and get approvals from our IG audience… No, what we only need is a place to find peace and real happiness.

Happiness Index by Sandro Mancini

Posillipo Which Makes the Pain Stop

The search for happiness, both individual and collective, constitutes one of the two fundamental drives accompanying the development of civilization. The second drive is the search for ways to avoid, or at least diminish, suffering and injustice, which amounts to much the same thing.

In Western civilization – particularly in Europe and North America – over the course of the modern era this search has developed into a narcissistic affair. Concepts like wellbeing, happiness and health have become intimate affairs between the self and the world at large. Ads for a newly opened day-spa exhort subway passengers to “invest in personal wellbeing”; yoga classes guarantee “personal health and happiness” for as little as twenty minutes a day.

Not by chance, individuals in Western civilizations often look beyond Western cultural borders in their search for happiness. Outside We- stern civilization the search for a happy life – or at least one as little beset as possible by pain, whether physical and spiritual – is structured to allow more room for harmonic complexities that take into account other, irreducible factors as well. It is not so much an issue of the individual’s relationship with the self, but of individual relationships with humanity, nature and the divine. The objective is a dynamic equilibrium of beauty and goodness, the Greek ideal of Kalokagathìa, understood as harmonious synthesis of vital, creative dissonances, beauty and goodness. When did the West become so unhappy? We live longer than ever before, have access to more education, to more effective health care, mobility and a wider range of work and entertainment activities than at any other time in the history of mankind. Why the collective long face?

In the wake of the Second World War, German-American philosopher Herbert Marcuse identified in ‘Eros and Civilization’ (1955), then exposed to searing criticism in ‘One-Dimensional Man’ (1964), a narcissistic trend toward a performance oriented society within Western civilization as the sole arbiter of life experience, as the sole value criteria for all members of society. Marcuse, along with other exponents of the so-called Frankfurt School (Adorno and Horkheimer in particular), intuited that this monotonous, obsessive logic would increasingly permeate affluent, technological society, crushing individual wellbeing beneath the yoke of consumerist desire. In short, these thinkers prophesized that the more we have, the less happy we’d become. This diagnosis from exponents of the Frankfurt School appears to capture 2016 Europe and America perfectly. One-dimensional man, condemned in contemporary society to be successful or crushed, robbed of the chance to cultivate his own personal inclinations, finds himself in the alienating position of searching obsessively for happiness and finding it slip out of his grasp at every turn.

Authentic happiness is impossible to achieve through the immediate satisfaction of instincts, or worse yet though a myopic desire to exceed and surpass others who are committed to the same chase and accompany us toward a mutual finish line. It has less to do with pursuing individual, self-centered desires than it does with fulfillment of the so-called ‘high’ desires. The Greeks called it Eudamonìa. The Romans (and later on Medieval Christians) called it Vita Beata, or Blessed Life. The human condition is always relative, and its meaning is woven into the relationships individuals establish with others and their surrounding environment, both social and natural, as well as (at least for those who can profess religious faith), a serene acceptance of the inevitable end of life.

One of the most enchanting corners of the city of Naples is called ‘Posillipo.’ The name comes from the Greek Pausilypon, ‘a resting place from danger’ or, and not alternatively, ‘that which makes pain stop.’ Already during Roman times Posillipo was considered one of the most beautiful places in the world, set like a precious gem in one of the most gorgeous gulfs the Romans knew, reserved for just a few privileged souls. Its name became an invitation: a opportunity for people to find pause from pain, a place for rest, comfort and support for the long walk that still lay ahead.

An Italian folk story, often associated with Posillipo and the Amalfi coast (though it could apply to many of the beautiful coves and bays nestled along the coastline around the Italian peninsula), drives to the heart of our contemporary quest for happiness: An American businessman, fulfilling his lifelong dream to visit Italy in his retirement, walks down to the beach at Posillipo early one morning to watch the sunrise. There he discovers a young Neapolitan boy sitting on a rock, fishing with a bamboo rod. The two enjoy the early morning sunlight, eyeing one another, and strike up a conversation. The boy is young, bright and sharp-witted. The more they talk, the more fascinated the American businessman becomes with the child.

“So what do you want to do with your life?” asks the businessman at last.

The boy shrugs. “You’re smart. You must want a career, or to work in politics, or to become a successful entrepreneur.”

The boy shrugs again. “It’s no use to go through life without any goals, son,” says the American businessman. “Look at me. I’ve worked my whole life. I’ve secured a fortune for myself, and made fortunes for others. I’ve commanded men and women, rode the high seas of finance and earned the respect of most. Now I can relax, enjoy my success. Now I have time for life’s simple pleasures, for this sunrise, these beautiful waters, this enchanting bay. You’re just a boy, and you have your whole life ahead of you. Don’t you want the same for yourself?”

“Yes, I do,” says the boy, smiling and jumping down off the rock to retrieve a fish tugging at the line. “But I’ve already got it.”

Sandro Mancini is Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Palermo and Director of the series “Itinerari Filosofici” (ed. Mimesis, Milan). Author of many publications, his inquiries have been mainly focused both on the contemporaneity (phenomenology, hermeneutics, dialectics) and the humanistic and Renaissance thought.

DRY takes up the challenge

Like each of us, even journalists and publishers are facing many battles at this time. As the storytelling of the present is likely to fall apart in the attempt of keeping up with a super digital and fast world, we need to identify the different topics and find time and space to deepen them. Our original mission of creating meanings which prevail on the overload of the repeatable, making future interact with memory, retains all its relevance today. So we made the decision to repost a selection of subjects and images from our First Issue Archive (April 2016) to show you how they lend a dramatic currency to the actual painful happenings, wishing it could help you to understand and sensibly reflect on the consequences of the virus global diffusion. We hope you’ll enjoy the reading.

The DRY team