Text and ph. by: Alessandro Benetti

Most towns of the Val di Noto, the southernmost of the three Sicilian valleys named by the Normans in ancient times, experience an enduring, somewhat disturbing daily confrontation with the ghosts of their past.

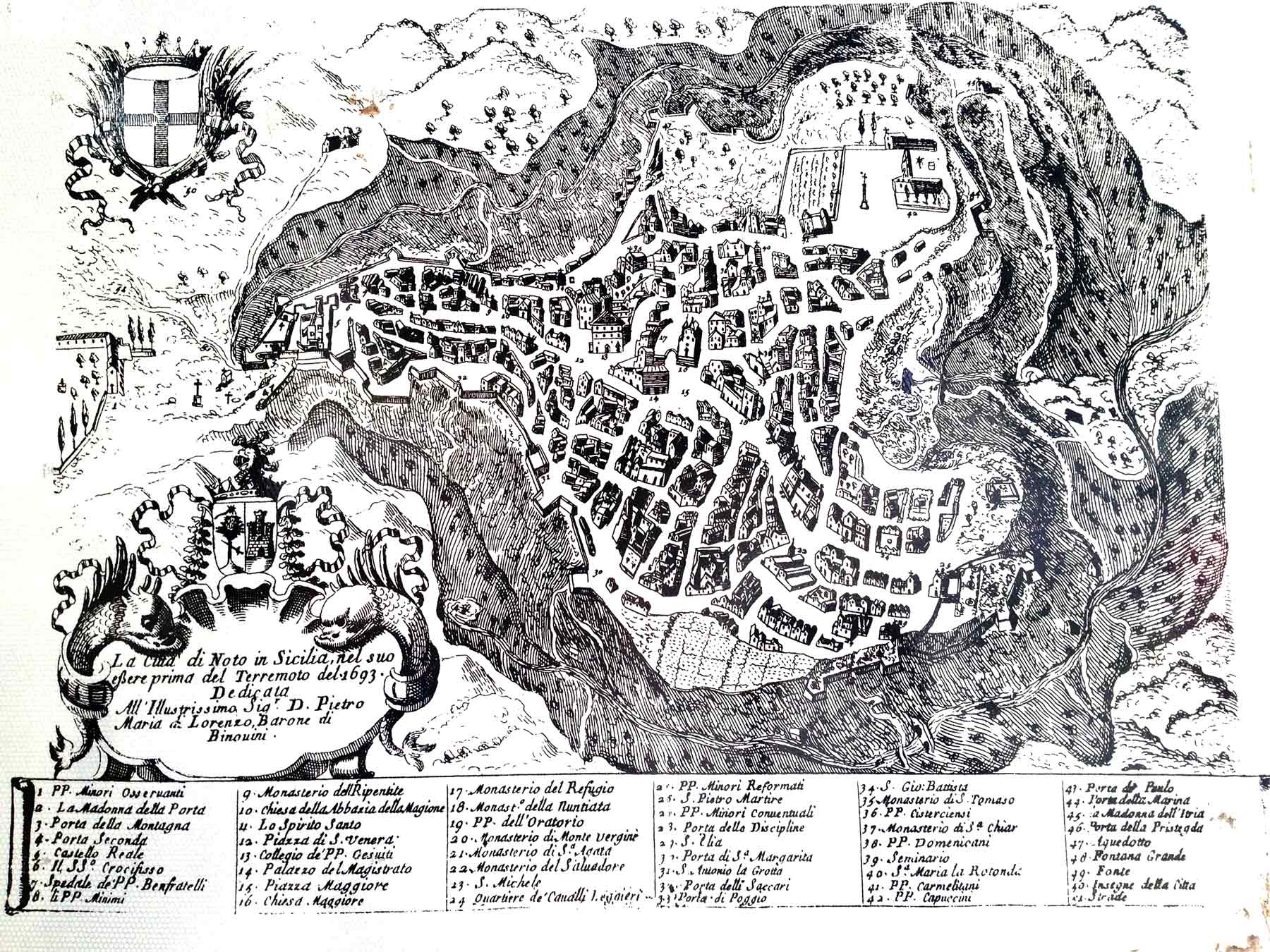

Baroque was all the rage in 1693, when dozens of then flourishing urban centres were razed to the ground by a devastating earthquake. A handful of architects – notably Rosario Gagliardi, Francesco Paolo Labisi and Vincenzo Sinatra – were given blank paper to shape their most extravagant and grotesque fantasies into the local light stone, creating off the table a whole series of brand new towns, that seemingly kept nothing but the toponymy of their predecessors. The de facto “corporate identity” of the region made of curvy façades, audacious bell towers, domes and heavily if not graciously decorated balconies dates back to that time and recently ensured the inclusion of its main buildings and historical centres into the Unesco’s World Heritage List.

Still, Val di Noto is much more than a bunch of “cute” Italian villages, now widely gentrified by crowds of Northerners, stuffed with all types of B&B and surrounded by a multitude of luxury country houses (all of which has its own undeniable charm). A more subtle presence persists, in the shape of a morbid symbiosis between the splendour and the geometrical perfection of each baroque centre and the disarticulated remnants of its Medieval ancestor. Pre-earthquake presences emerge in the spiralling alleys of Ibla, rebuilt over itself as the precisely dimensioned grid plan of a modern Ragusa was unveiling on one of the adjacent hills; the ancient, dominant centre of Modica still watches over the new town that was born at his feet, and the two later joined to shape the city of today; the few survivors of Noto, instead, were forcibly moved to a new location, consigning the former town to perpetual oblivion.

Today, reaching to Noto Antica, 8 km to the north-west of the city, means getting away from the crowds and sinking into the timeless indolence of the Sicilian inland. Some attempts were made in the recent past to transform the site into a touristic attraction but to little or no effect, and the few information panels and wooden fences installed are also quickly turning into ruins. Once inside its imposing walls, still clearly showing despite centuries of abandon, at first Noto Antica might disappoint the hasty visitor, blinded by dazzling sunlight, which finds himself plunged in an ordinary landscape of “macchia mediterranea”. However, as he ventures through the site, pacing the unpaved track that used to be the city’s main road, and coming across few fragments of anonymous walls pointing their bonnet on its sides, a different reality will progressively show to his eyes. Protected by the lush vegetation, hidden in the twilight, millions of stones can be spied, accumulated to form a continuous, dense and extraordinarily thick mineral undergrowth. An odd intuition comes to mind, assuming that each single block might still be laying in the same exact position where the tremor hurled it in 1693.

Noto Antica is a weird archaeological area, indeed, and its fascination lays exactly in its unexploited potential: everything is still to be (re-)discovered here, and not much has been explored, interpreted, protected or restored yet. Hopefully, nothing of this seems to be forthcoming, and Noto Antica will stay as a surreal corner of one of the dreamiest regions of Italy, a land which has been shaped for ages by the incessant and often accidental overlapping, combination and destruction of the multiple layers that make up its identity.