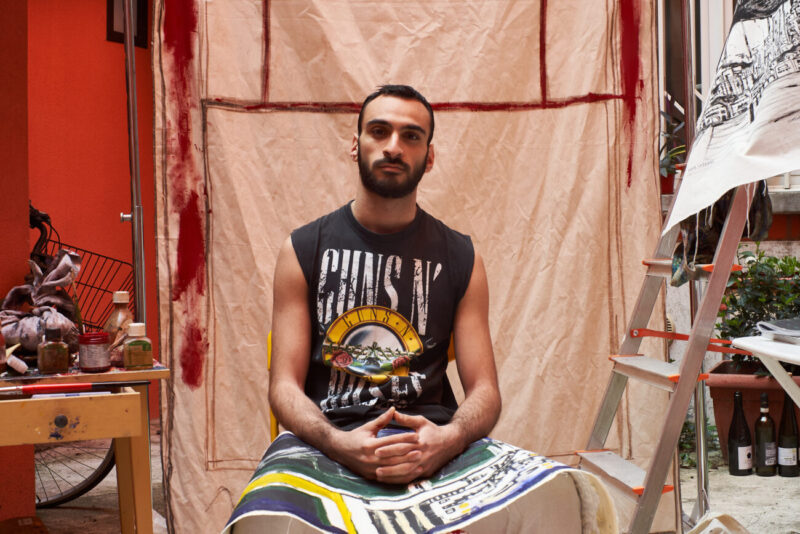

In the contemporary art world, inspiration and innovation merge to create artworks that reflect the human spirit through a visceral representation of urban architecture. In this perspective, I had the privilege of interviewing the young (and my contemporary) Rami Lazkani, a talented Lebanese artist whose creativity has already left an indelible mark on the Italian and European art scene. With the unmistakable warmth that characterizes him, he opened the doors of his home to me in the late morning, giving me a unique experience of closeness and sharing. I was immersed in his world as he introduced me to it through all the objects he uses every day in his studio, allowing me to fully immerse myself in his creative process and daily sources of inspiration – but also of his most fleeting thoughts – which, to be honest, were almost perfectly compatible with mine, being peers who, in one way or another, work in the same field, that of art.

Through his work, Lazkani conveys complex emotions and reflections on life, offering a unique glimpse into his worldview; a fascinating journey into the artistic universe of one of the most promising talents of the Middle East.

Between a Lebanese fattoush and a shawarma for lunch, we engaged in a friendly conversation, which further enriched my understanding of his world.

What brought you to Italy, and what made you choose bustling Milan specifically?

I came to Italy to study. But i never went to school. My university in Lebanon had a good reputation, and I was a brilliant architecture student, it was easy getting the acceptance at Politecnico di Milano. Also a lot of my Lebanese friends live in Milan, which was more tempting. My current flatmate was also super helpful to help me move, we’re both Lebanese, but we met in Poland. He told me how beautiful Milan is, Porta Venezia, where we live. Frenetic? Yes, now I got it. Milan is definitely a looney-town: “Mom come me up I’m scared”. Joke. Or not.

Regarding that, what do you like about this city? And what instead you can’t stand? What relationship do you have with it?

I love it when it’s sunny (like the day we met!); I’ll say it again: when it’s sunny there is nothing to hate about Milan. I love the girls who serve me coffee in the morning; we’ve become friends. My neighbours ask about me when I’m gone. It’s weird, but I feel a sense of belonging. Milan also reminds me of Beirut. At 7 PM, when people fill the bars and restaurants, there’s a vibrant way of living, definitely fast, which is what I despise. Controlled by traffic lights and not skipping a green light. Breathe, man. But I understand; office life can be daunting. That’s why I never wish to work in an office. I’ve also become friend with the guy who sells flowers in Piazza Otto Novembre. I love flowers, and I try to get some every day.

Another thing I despise is how flat the city is. It feels like a prison, or illegal to get a view of the city from a bird’s perspective, unless you live on the top floor and have an open view. But I’ll tell you the truth, since I started speaking Italian (according to friends), life has become much simpler, and the sense of belonging has become stronger.

What is the relationship you have with your home country, Lebanon?

I love it. Maybe at a different time, I would love to go back and live there, in the mountains or by the beach. It’s tough to talk about home. I deal with the concept of home in my work all the time. After 2 years away, I’m not sure if I can call it home. My parents’ house? Maybe. It’s always there, ready to hold me together. But I’m not made of the same pieces anymore.

From there, what did you bring with you, metaphorically, to Italy?

Mammamia, guys.

The hummus, of course. Also, I guess whenever a Mediterranean comes here, he gets called Habibi. Imagine walking in the street and everyone calling you Habibi. With an H, not a Kh. That’s lovely. I think we did a great job. We spread love. I brought openness to learn the Italian culture, I cook like you do, I live like you do. However, always rooted in my Arab origins. It’s like uploading and downloading a set of skills, rituals, lifestyle.

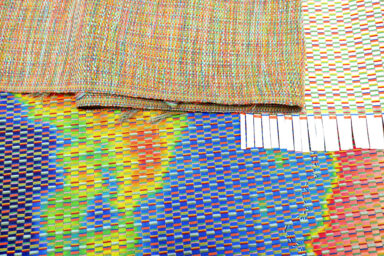

During your career, you’ve painted and illustrated on various materials, in different ways, over the years. What is the medium you prefer to express yourself with?

I think what I am beginning to understand is that I love paper. The material, the receiving end. It tells you what it needs; you just need to find the right way to approach it. Paper is usually where I start from: different paints, pens, and stencils yield completely different feelings.

Yours, as evidenced by the works related to architecture, is an excellent photographic memory, which allows you to bring back and evoke in people’s minds cities and the feelings associated with them immediately: have you always had this particular ability to visually reproduce memories belonging to you, or is it something you developed over time?

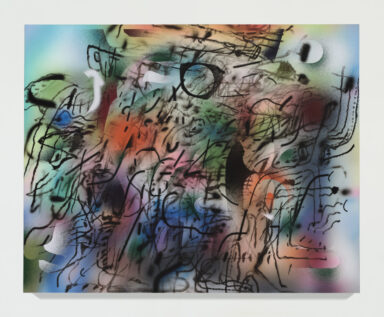

It is definitely an ever-evolving record player. You know, as time passes by, with my eyes wide open, lights on and off, my senses are stimulated. Like a rolling camera, it keeps registering. It registers everything. Recalling is a completely independent process. When I am painting to conform to the artist character that I have created, this avatar, I need to filter the footage to pick the scenes that have to do with architecture. And it is easy. It is even easier when I relate the scenes to people: “Ah, here I met this and this, and there was this arch with three dots on top, a rectangle on the side, a circle on the right”; the simpler the words are in the recalling process, the easier the conversion to lines on paper. When I am off character and do work that is unrelated to architecture, the filters are off, and I am free.

Your art is characterized by a deep connection to your homeland. How do you think your time in Italy has influenced your art? Do you think it will in the future, perhaps if you change your place of residence again?

My art has matured, you can see it. I am increasingly in search of understanding the catalyst of this journey. Yes, it means asking all the existential questions about why art exists.

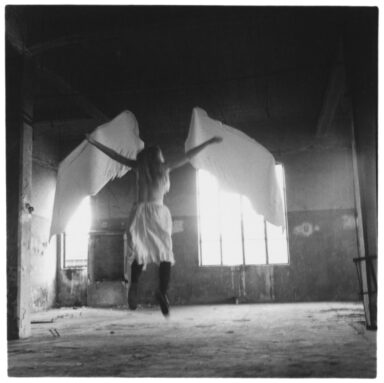

Why am I stuck painting a house with 3 arcs? Why do I force myself to sit down and envision this house in every possible situation? I am trying to hold it together, the notion of a home. Not the physical one. My work has always been an archive of Lebanese architecture, mainly its villages. I was at home. I didn’t have to simplify my work. It was widely appreciated in Lebanon, easily recognizable. It didn’t hit me that I was searching for a home, not a house, until I moved to Milan and understood the reason why my art is appreciated in the West is because it looks “exotic.” I don’t want that. I needed a couple of lines that, when put together to form this house, could tell the stories that all my more detailed work, the archive, has not been able to tell. I paint a house with a sun now that can pump a wave of pure serotonin into your neurons. The human experience is beautiful. I am giving my house the chance to go through this human experience. When it sails by itself on a boat, or sits in a deep forest, or grows wings. We know how that feels. It needs to know it too.

Arches, within buildings, within clusters, within cities. Both in Europe and in the Middle East, for some time, building is not just an option and not always beneficial. What effects has gentrification brought to Lebanon? Do you see Italy in the same way?

This is a tricky question. I attended architecture school. In these situations, you need to consider many factors.

First, the consent of the people to transform their quarter/neighbourhood. Second, the nature of the project. Is there a new proposal? A community project that considers the needs of the inhabitants? Does it integrate them as key players in the new urban project, as decision- makers? As workers? Even as just inhabitants who use the space as intended?

Third, does this further isolate them? Or is it simultaneously expanding the transportation system? Will there be additional fees for transportation? The criteria to judge this “gentrification” have become extremely detailed in recent times. Cities in the modern world expand, and money plays a significant role. Money doesn’t care about who pays rent. Money wants more money.

On your Facebook page, which you probably haven’t used in a while, there’s a sort of statement against portraits, in the description. What do you think is the right balance to avoid compromising and having to comply with others’ (or market) demands, yet still achieve success?

I still don’t accept portraits. Simply because I don’t have that skill. It takes a lot of training. There are artists who are extremely skilled in capturing human expression, the right proportions. It is a very personal approach. At that time, I was still growing my platform.

And people thought art meant portraits. The only things they would pay for. A bit narcissistic, to be honest. But who am I to judge? I would like my portrait painted too. Do you know someone?

To answer the second part of the question, I think there is no easy way. Art unveils pages of intense pain and love. Art is a direct reflection of how deeply you delve into hell and heaven. Hell, utmost, as it brings up the most relatable human states. You need to capture that in your work, have courage. And do your homework. People want to see impressive hours of work. They care about the effort, at least in select pieces. When your homework is done, you can make a stroke that moves crowds.