Unraveling the Controversy and Cultural Significance of Italy’s Most Infamous Folk Song

Words TOMMASO FALOCI

Public discourse often ignites when the topic of “Bella Ciao” arises: the mere decision to sing it, or not, immediately reignites the timeless debate between opposing factions. Although traditionally regarded as one of the cornerstone songs of the Resistance, ideally, “Bella Ciao” should foster unity rather than division, symbolizing liberation and resistance against oppression. However, as we have witnessed, it has become a contentious issue within our society: while some embrace it fervently as a badge of belonging, others disdain it, viewing it as a venomous anthem of partisanship. It represents a quintessentially Italian paradox, whereas abroad, it is interpreted simply as an anthem of freedom. There exists no documentary evidence of the folk song’s existence until the 1950s. Initially, it was believed that “Bella Ciao” originated from a tune sung by rice-weeders, but Italian historian Cesare Bermani argues that this is a later composition, purportedly penned after the war by the rice-weeder Vasco Scansani di Gualtieri. Although the lyrics of their song bear resemblance, their version of “Bella Ciao” laments the fading youth behind such arduous labor. It is purported to have been composed in the vein of “Fischi al vento” / “Katjuša”, a famous Soviet folk song that served as the official anthem of the Garibaldi Partisan Brigades.

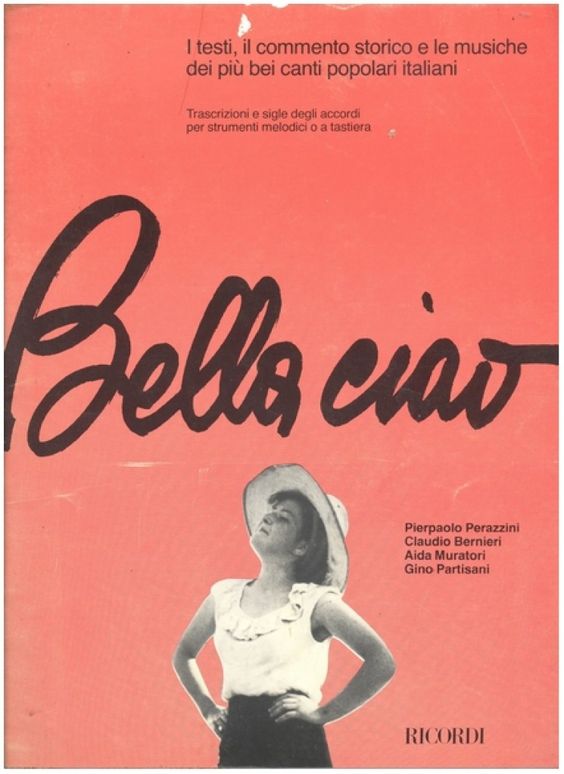

Delving deeper, “Bella Ciao” encompasses three distinct cultural works. Firstly, it is a song sung by partisan formations in the waning moments of the liberation war. In Italy, it is regarded as the unofficial anthem of the nation’s anti-fascist faction. The decision to sing or abstain from singing “Bella Ciao” reflects a precise political stance, igniting numerous debates and conflicts in the 21st century. Additionally, it serves as the title of a show featuring a selection of Italian folk songs, conceived by ethnomusicologist Roberto Leydi and directed by Filippo Crivelli, with performances by the group Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano (NCI). Last but not least, “Bella Ciao” also refers to an album released by the label “I Dischi Del Sole” in early 1965, documenting the aforementioned show. This album, reissued over time, has become a cult classic in the national discography, shaping the musical and cultural perspectives of activists, scholars, and musicians. Its resurgence in the 1960s can be attributed to the “folk revival” movement, with a pivotal moment being the Folk Song Festival in Milan in 1965, where “Bella Ciao” was prominently featured. During this era, it was adopted by students and workers amidst the clashes of 1968 and the “Hot Autumn”. Artists such as Giorgio Gaber (who performed it on television in 1963) and Fabrizio De André – drawing inspiration from its folk versions (both lyrically and melodically) in songs like “Carlo Martello” and “La ballata dell’amore cieco” – contributed to its mainstream success. Milva performed it on Canzonissima in 1971, while the Italian singer-songwriter, Yves Montand, made it famous even beyond the Alps. However, this does not explain why it is sung today, in translated versions, by Chileans in revolt against President Sebastián Piñera, Kurdish fighters in Rojava, or Iraqi protesters opposing the policies of Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi.

Examining the trajectory of the cultural project centered around “Bella Ciao” provides a valuable opportunity to reflect on the purpose and aspirations of cultural musicology in the contemporary context. It allows us to explore the boundaries and test the validity of the categories we use to understand music and the political landscape in Italy, while also delving into our collective identity of leftism and anti-fascism. The enduring perception of the song as a tool of resistance and dissent today is partly attributed to the three aforementioned cultural elements associated with “Bella Ciao”: a music album, a theatrical show, and a song. These specific cultural moments, immortalized in time, continue to contribute to the ongoing resistance.