Pietro Fogliati’s sensory machines at Tempesta Gallery

Piero Fogliati has dedicated his life to researching perception; his ingenious and poetic installations, in which art is movement, light, retina and sensations, are understandable only when experienced. He was born in Canelli in 1930 but chose Turin as his home. Starting in the 1950s, he devoted himself to the visual arts, but his passion for science and technology soon took over. Exploring the perceptual spectrum and natural phenomena, Fogliati built machines endowed with a sublime and refined aesthetic connected to the visual-acoustic sphere.

He combines beauty and perception, man and machine living in an ideal place: the Fantastic City, a vast urban intervention project in which sounds, lights, atmospheric elements and hydrogeological ecosystems are transformed into aesthetic and sensory experiences.

From this experiment comes Tempesta Gallery’s City Poetry exhibition, which aims to actualize the figure of the artist-engineer and rediscover Piero Fogliati’s entire body of mechanical works. In a dialogue on the contemporary that the gallery constantly poses in its research and reflection, it addresses, through Fogliati’s themes of the ambiguity and complexity of the world, current contrasts: the industrialized city now megalopolis, the development of technologies and the consequent process of the drying up of nature, questioning the design of the landscape but also the urban structure and its housing patterns. Fogliati proposes a handhold, and offers a cue to safeguard “place” with imagination, is this path still viable today?

The first room, entirely dedicated to Fogliati’s sonic and iconic works, is designed to create a real dialogue with the noises of the city.

It begins with the acoustic machines, the Ermeneuti, two alpaca tubes, slightly curved, capable of modifying all external noises by transforming them into an ever-changing and engaging continuous sound. These installations derive directly from the design of the Noise Auditorium, which in the context of the Fantastic City, was to be an environment-instrument corrector of the external din. Within this environment, the external noise, in its total complexity, was to be heard, filtered and transformed into a new, ever-changing and unique sound event. Next comes Latomia, similar to the Hermeneuts, which differs in the way the sound outcome is produced. It consists of a curved tube this time not suspended but resting on the ground and of different sizes. For Latomia he uses different materials and experiments with alternative sound productions by inserting some liquids such as water, oil, and even glycerin. The result is achieved by the interaction of the shape, the liquid, and the amount of air introduced.

This is followed by the Fleximophone, or also Sonic Sculpture, which consists of a series of regularly arranged springs made of harmonic steel and attached to a plate hanging from the ceiling. This allows the work to present a dual sonic and visual outcome. Fogliati says he chose the springs because he had begun to take into account, in the sculpture, “the fact that it had to be physically light.”

He moves on to the visual approach with Evolving Eurythmy. “The purpose of Evolving Eurythmy was to be able to realize the vision of a body suspended in a vacuum, endowed with a particular movement that was not rigid, but somewhat imprecise and gave the impression of vitality.”

Following two of the artist’s most important works, which claim heights and volumes in the room, is the breathing machine, a work that most embody the author’s artistic utopia of giving life to machines. An essential and “minimal” installation in its mechanics is composed of two basic parts: a producing body and two receiving and emitting tubes. The other work is the autonomous field that resonates like an orchestra conductor far and wide in space creating different symphonies. As part of the design of the Fantastic City, Fogliati had thought of making a device that could self-program itself in an ever-changing way, so that it would never present an event the same as itself. This device, like a sort of control tower, would then trigger the machines ensuring the non-repetitiveness of the outcomes of each environment.

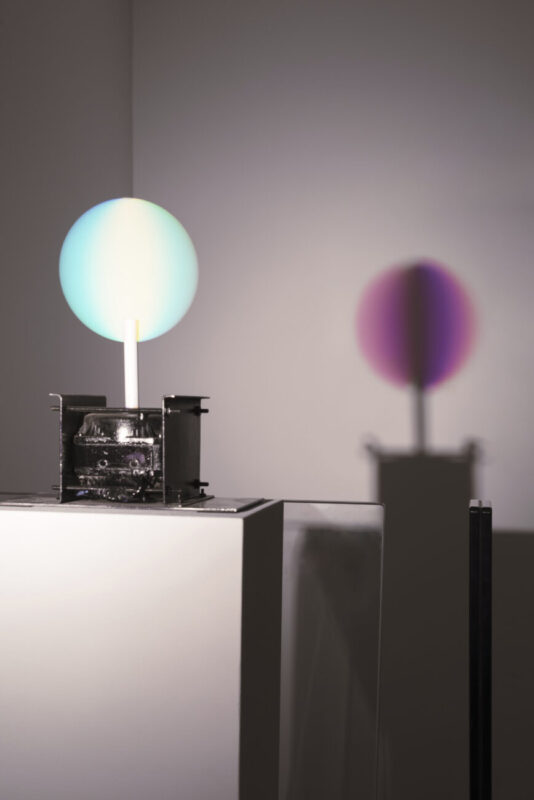

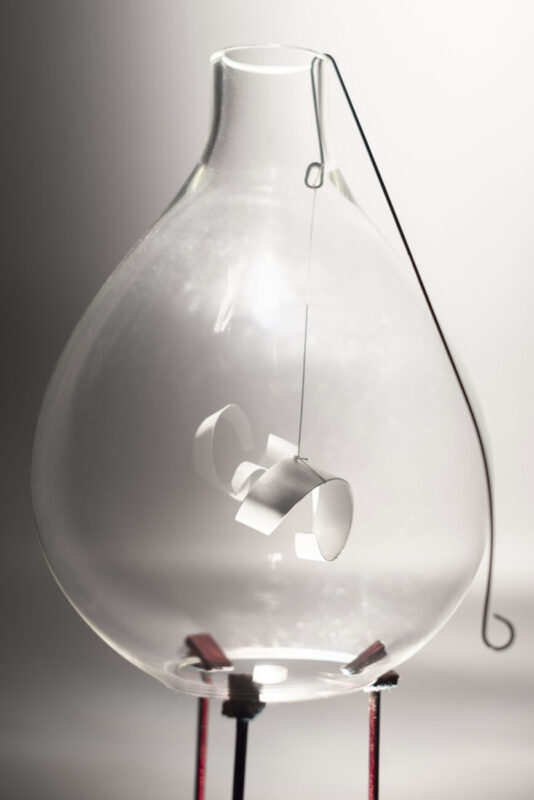

The protagonist of the second room is the kinetic chrome detector, a work consists of a synthetic light projector that illuminates a white elastic rope that oscillating shows spherical shapes and colorful geometries in the void. Next to it takes its place the Virtual Real, consisting of a hand-blown, very fine glass ampoule placed over a projector, specially built by the artist, inside which 2 objects have been placed but, as the title itself anticipates, one object is actually real, the other is its virtual copy, equivalent but specular.

The passage into the third area, the flight of stairs leading to the mezzanine, is greeted by the Mechanical Prism composed of a Synthetic Light projector and an aluminum support in the shape of a white-painted, vertical disk, rotating on itself at high speed that collects light and reflects it by breaking it down into its composition colors. The white disk (precisely the “mechanical prism”) is colored in the primary hues of orange, violet, green, and blue, and the transition between one and the other is never sharp, but occurs by gradation.

The last work, in order of visit, is a series of Luminous Successions capable of disorienting the viewer and disrupting the physical laws of “matter”: beams of light point at the disc and, thanks to the movement, generate a deforming and multiplying effect that transcends the boundaries of the forms that appear perfectly intersected. The luminous outcome is the impression of observing a sculpture of light that changes shape and number in increasing/decreasing successions.