THE PURSUIT OF PLEASURE, THE GAME OF LOVE.

IN THIS ISSUE:

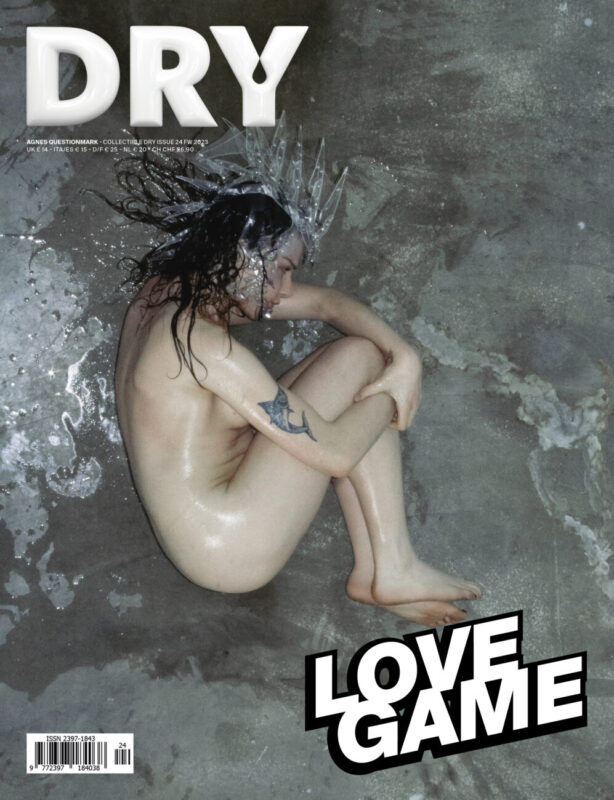

AGNES

QUESTIONMARK

MOSCHE

BRAKHA

AMBRA

CASTAGNETTI

Óscar

Carretero

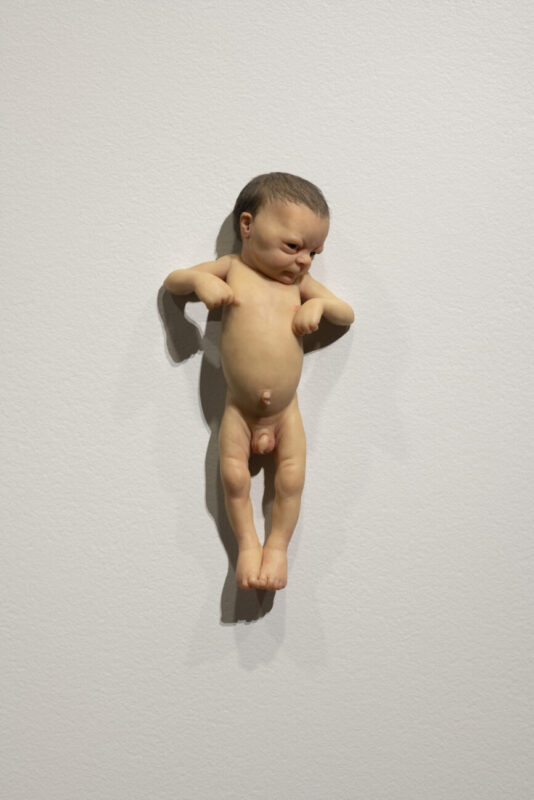

RON MUECK

ANTONIO

LOPEZ

PAUL

CARANICAS

BETONY

VERNON

BRUCE

LABRUCE

SLAVA

MOGUTIN

CCH

COLIN J.

RADCLIFFE

GABRIELE

ROSATI

LIAM

GILLICK

SLAVA

MOGUTIN

LIBERTINISM OR THE MISFORTUNES OF VIRTUE

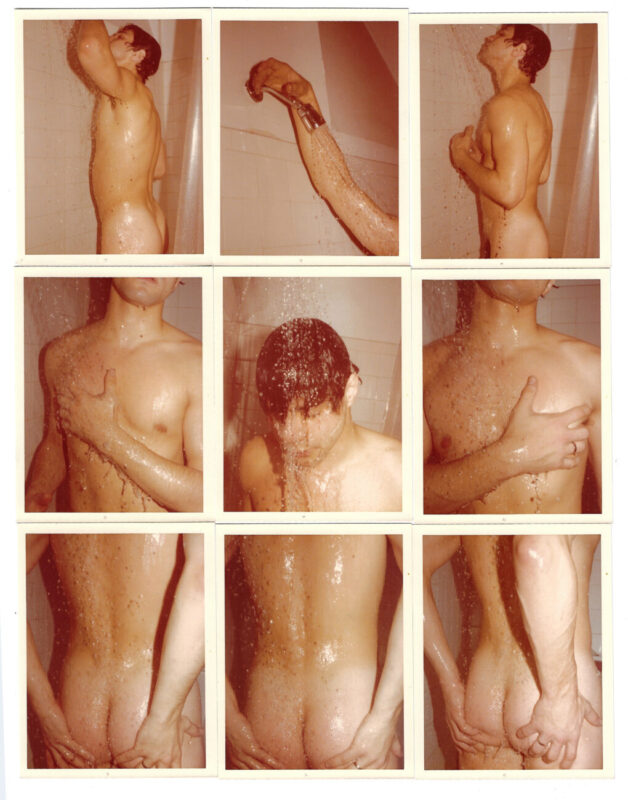

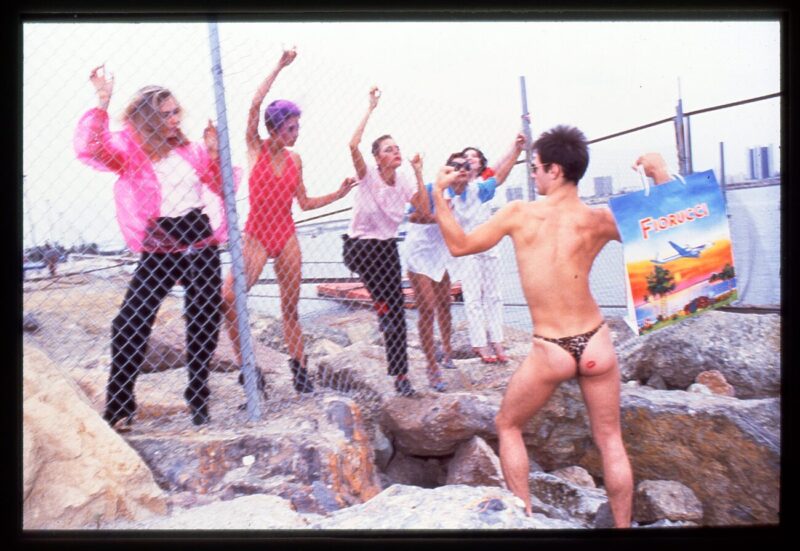

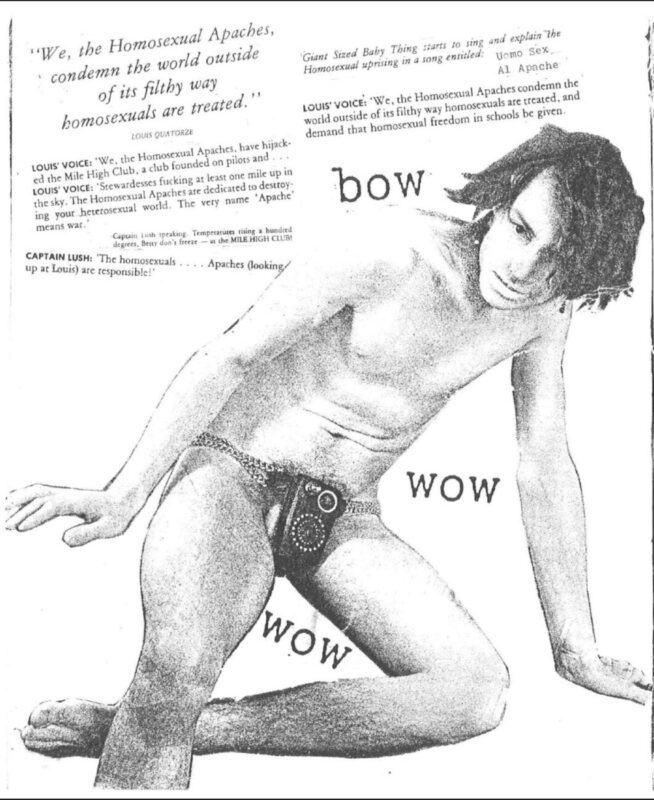

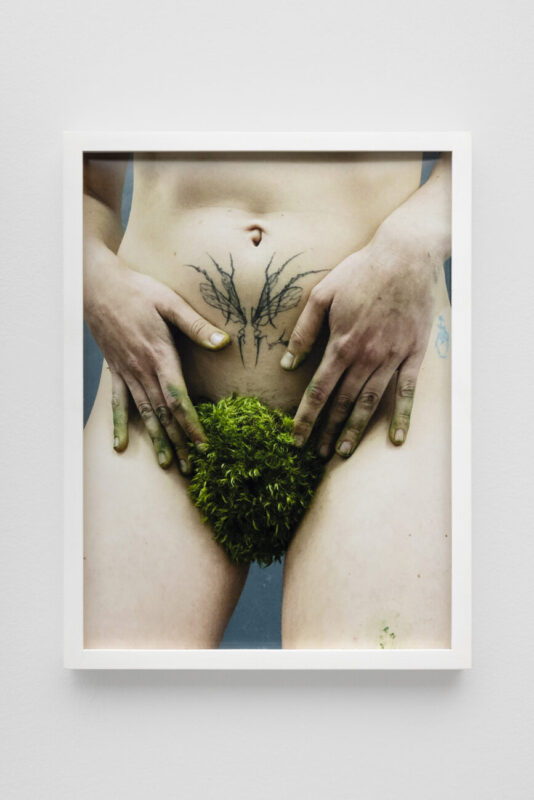

In this issue, the second of the year dedicated to the theme of play, we’ve ventured into the uncharted boundaries of freedom with the guidance of remarkable individuals. Yes, for the game of love leads us to explore novel pathways, to transcend our own limited perspectives, and to embrace the concealed facets of our identities. We’ve unearthed that the game of love can be a revolutionary act, a form of political defiance. It beckons us to delve into abandonment, to reject the existing order, and to yearn for a reality that encompasses all. Be sure to read the interviews with Betony Vernon and Marilyn Fitossi, the former being a creator of jewelry and a sex therapist, the latter a brilliant costume designer of “Emily in Paris,” revelation of the trend that wants fashion depicted through the characters of successful television series. Then there’s Bruce LaBruce, a pioneering and irreverent icon in the realm of transgressive pornography, a revolutionary in his own right, as his work transcends the confines of the marketplace. And let us not forget the narrative by Paul Caranicas, elucidating the tale of Antonio Lopez – alongside his life and art companion, Juan Ramos – the brilliant illustrator who left an indelible mark on the imaginative 1980s with his glossy and elegantly provocative depictions of men’s intimacy. Other contributors dance across our pages in a symphony of references, allusions, and explicit representations, yet they never succumb to voyeurism, as these expressions are experienced through the prism of art and form.

In this manner, life bursts forth, as life, after all, is an amalgamation of freedom and libertinism, leading us to challenge the shackles of societal conventions. These conventions are inextricably tied to the times in which we dwell, rendering them subjectively mutable across epochs. In the classical antiquity and well into the late Renaissance and Baroque periods, the depiction of male anatomy was both permitted and accentuated, but the 18th-century society, known for its extremely liberal customs, embraced more or less openly, the flaunting of debauchery, at least within certain affluent echelons.

Liberation and thus sexuality were often harnessed as social forces, interpreted as class struggles. In fact, even today, despite the vociferous proclamations accompanying the #MeToo movement, countless women and men, perhaps more so today than ever before, capitalize on their sexuality and allure, thanks to the technological means provided for that very purpose, for opportunities that the unapologetic use of their bodies as instruments of persuasion affords – thus, a political act. The feminist cry, “My Body, My Choice,” is nothing less than the skill exemplified by someone like Madame du Barry, who gained entrance to the morally bankrupt court of Versailles, as a well-known illustration, ascending from the boudoir to the pinnacles of power.

However, this is not a shortcut; it is a game that demands determination and fortitude in the pursuit of one’s objectives. It necessitates culture, education, and intelligence. Like a game of skill, the life of a libertine unfolds on the chessboard of existence. It requires the audacity to challenge conventions and to avoid succumbing to banal commodification. For the true libertine’s game is grounded in an acute awareness of the pretenses of others. And in this game, victory is assured. SILVIA MOTTA

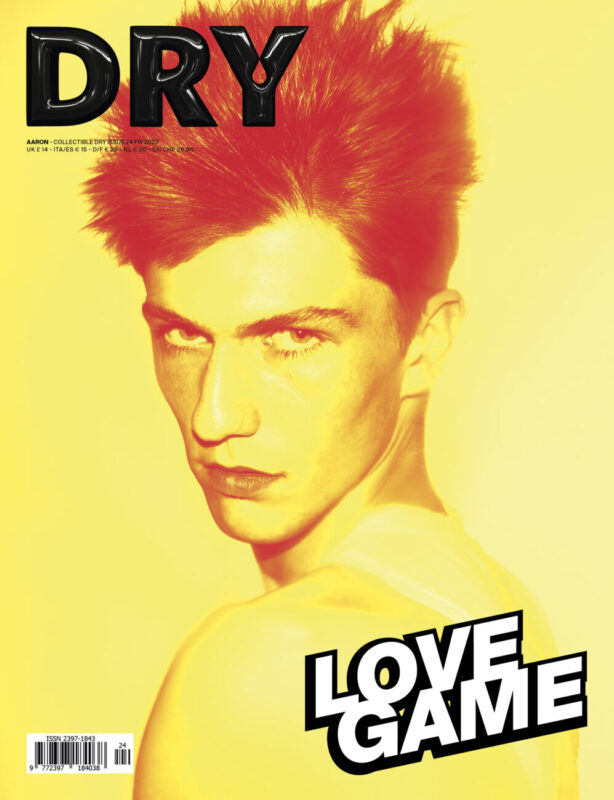

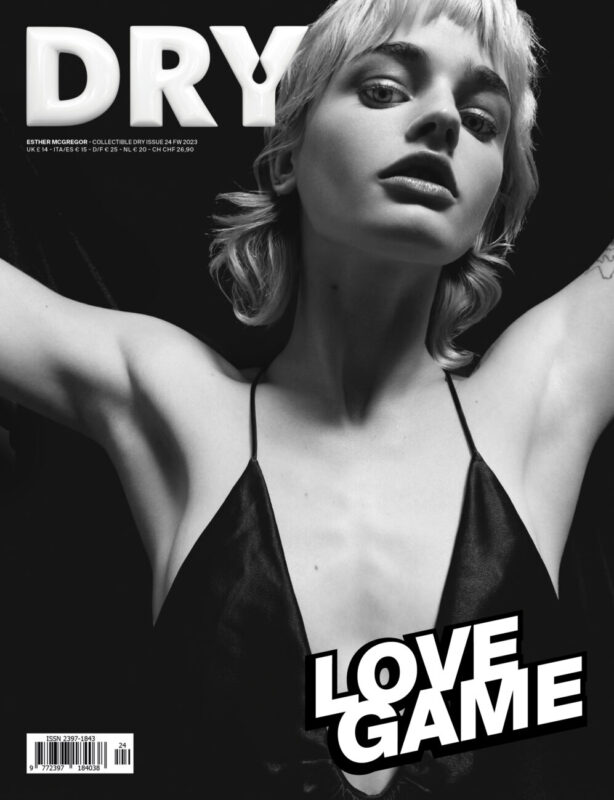

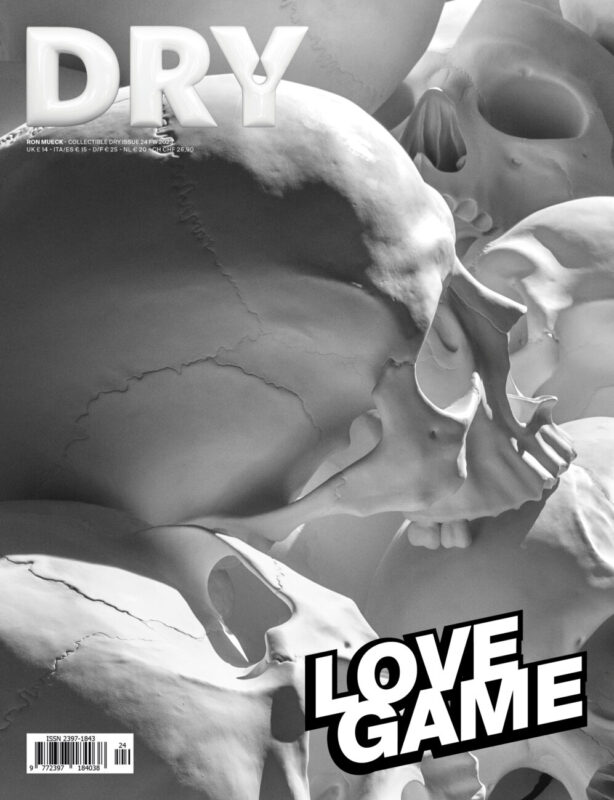

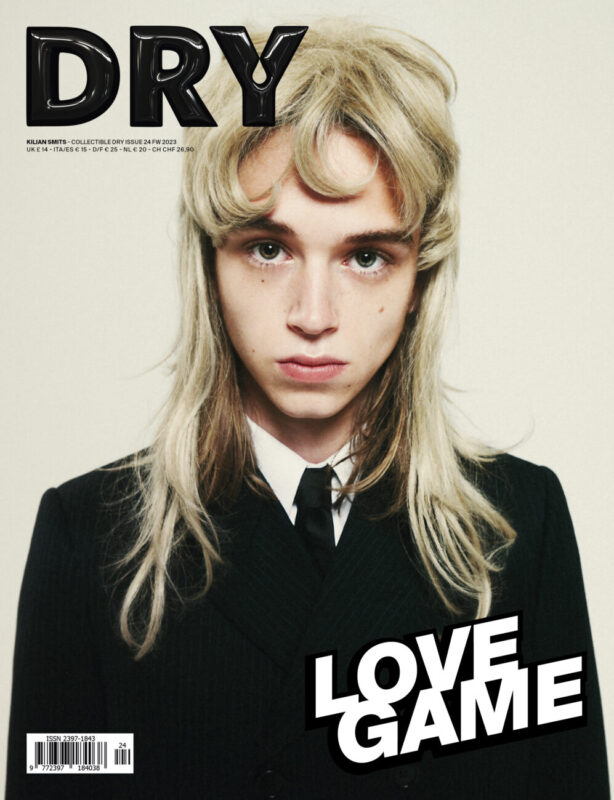

THE COVERS

Don’t Repeat Yourself

AGNES QUESTIONMARK

ANTONIO LOPEZ

GABRIELE ROSATI

COLIN J. RADCLIFFE

FIORUCCI XXX

BRUCE LABRUCE

GIOVANNI DE FRANCESCO

COLMAR

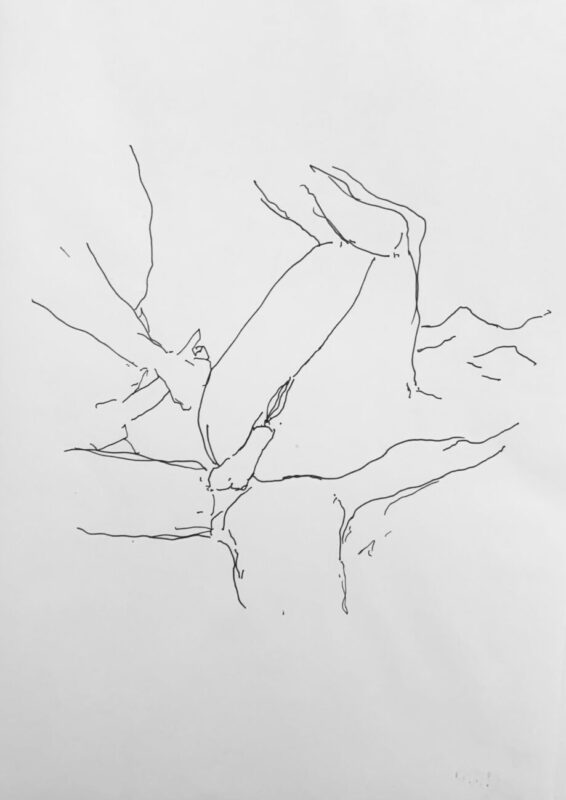

AMBRA CASTAGNETTI

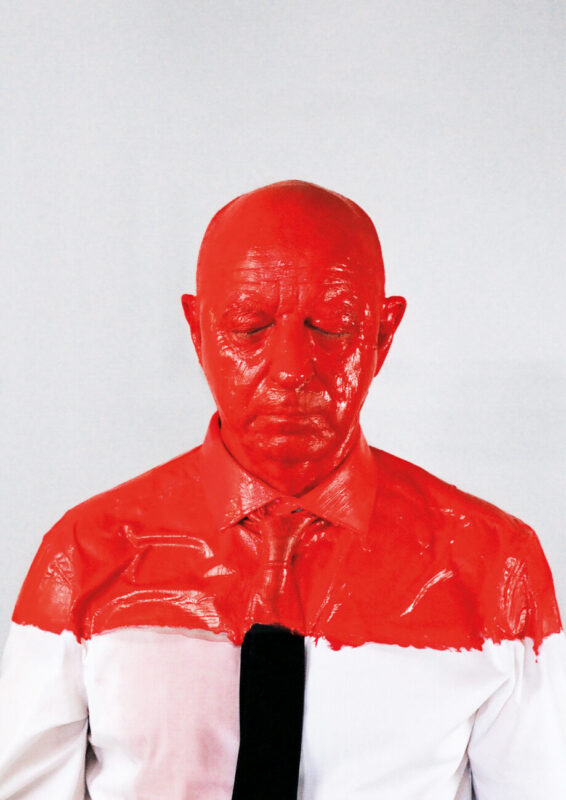

RON MUECK

ESTHER MC GREGOR

CCH

MARC DE GROT

SIN WAI KIN