On art, social media and contemporary society with the young painter Adelisa Selimbasic

Text by Gianmarco Gronchi

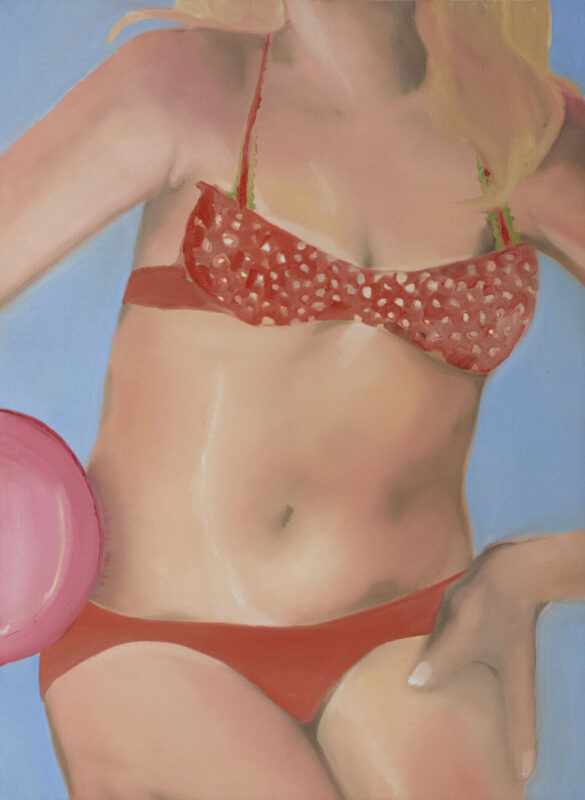

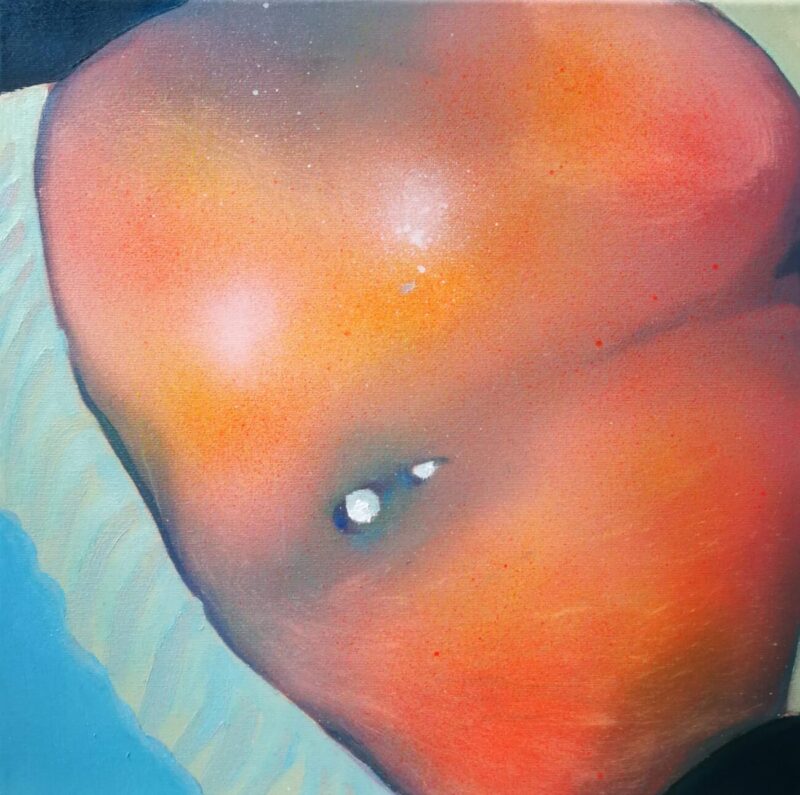

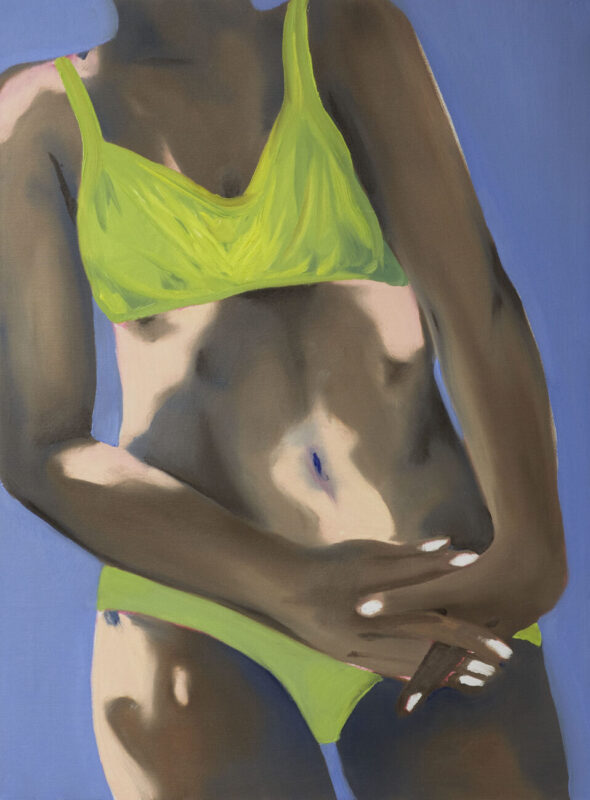

There is something in Adelisa Selimbasic’s painting that captivates the senses. In these times, in the age of immaterial art, it must not be easy to stand in front of the blank canvas with a constructive attitude, especially if you practice a genre – figurative art – in which the ramifications of an often short-sighted obscurantism seem to persist. It is perhaps no coincidence that two of the greatest masters of the post-World War II period – Bacon and Freud – chose the path of figuration. Painting has died and risen again and again, and the works of Adelisa Selimbasic, artist born in 1996 and trained at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, seem to tell us that oil painting is still capable of opening up spaces for dialogue, in an iconic and burning way. And as in Freud, Selimbasic’s attention revolves around the body, particularly the female one. In our eyes, it seems that this young Bosnian-Italian painter’s work is not a feminist declaration of intent. The bar seems to be set higher and it probably concerns the possibility of renegotiating individual and socio-collective physical perception. For once, colour does not seem to be the lure of many meaningless pop-isms, but a wisely used tool to resolve the search for a definition within painting. What are the identifying characteristics of the human body? What are its potentialities? These seem to be the questions that animate Selimbasic’s works. The answers can only be found in the stretch marks, in the wrinkles, in the waning fat of her women, in those bodies that seem to tell us that that is reality, that is the human material. And it is precisely there that the fire of painting flares up.

Gianmarco Gronchi: First of all, I would like to ask you how your painting come about and what your cultural references are.

Adelisa Selimbasic: For me, it is important to emphasise my origins. I was born in Bosnia and grew up in Italy, and this brought me to confront two different mentalities. In Italy, women are more emancipated, while in Bosnia they are still tied to a patriarchal society. For this reason, my research focused on women’s bodies in order to give voice to them not only as subjects in society, but as bodies, as physical presence. When we talk about physical perfection, we often tend to think about the female body, identifying it as an object. That is why I started to represent bodies in a mischievous way, alluding to sexuality and showing breasts, buttocks and erogenous zones, but with the idea of investigating them as forms, getting away from that pornographic categorisation of women’s bodies. At the beginning, even my own family members were doubtful about whether I was portraying these naked or semi-naked bodies nude. Today, after three years, I have managed to convince them of the meaning of my research.

As you can see, I am very attached to colours, which allow me to focus on details. At the moment I am obsessively focusing on the rendering of a sick, almost emaciated skin. As you come closer to the canvas you discover that there are different colours that contribute to the rendering of this detail, precisely because the skin absorbs and reflects light, varying in chromatic intensity. It is never just one colour. That’s why, from a technical point of view, I’m working on using several colours that melt into each other to render the skin.

GG: Maybe it’s just a suggestion, but looking at your work, it seems to me that you can see a friction between the skin of these bodies, the shadows that characterise them and the backgrounds, which you describe using very flat colours. A sort of visual counterpoint, a visual tension that highlights the bodies.

AS: That’s exactly what I’m looking for. I use this chromatic contrast to draw attention to physicality, to the centre of my research, which is skin and flesh. Moreover, my women never have a face, or if they do, it is ambiguous. I believe that the body is a very powerful communication mechanism, the most innocent and sterile one we have left. From a very young age, we are used to hiding our emotions and controlling our facial expressions, but the body communicates without us being aware of it in a different and uncontrollable way. This is why the body is a sincere means of communication. I have noticed that the first point of attraction of a person, for me, is the way they occupy space and the posture they have. Eye contact presupposes a rapprochement, but this happens if there is something that attracts us, and in my case it is the posture, the body, that gives an identity from a character point of view.

GG: There is an attempt to give the body back that word, that expressive and communicative capacity that is partly denied.

AS: In my works, poses are not random, because they are part of the narrative of the subject I am representing. The same goes for the clothes. I like to represent the fashions of the moment. Clothing is another means of communication, and by dressing we make a lot of our personality clear. Clothing is a very powerful weapon that allows you to express your inner self in a very intimate way. This is in line with my research, because if used intelligently, clothing can enhance those bodily characteristics that are generally seen as imperfections.

GG: Nowadays, art makes use of all kinds of means and mediums. Yours, however, is a very precise choice. How do you relate to this medium?

AS: For me, painting is exciting, and I find interesting how a different world is created in a very thin surface that is hung on a wall. I think seeing the work behind it gives the painting value. From my point of view, painting is a very spontaneous, instinctive medium and I don’t know if I really chose painting or if it chose me. I can say that when I was asked at the academy which specialisation I wanted to pursue, I instinctively said painting.

GG: The first time I saw your work, some masters of figurative art, such as Domenico Gnoli and Alex Colville, came to mind. Styles change, but I think there is still a subtly disturbing vein, a dissonance that runs underneath the surface and reverberates from canvas to canvas to create unprecedented visual disorientation.

AS: I certainly look a lot at 20th-century and contemporary painters. I like to keep up to date as much as possible with what is happening in the field of art, because otherwise it would be like working in the dark. It happens sometimes that on an unconscious level there are references in my paintings and I like it when a visitor notices similarities with another painter. Some people might not appreciate it, but I am happy about it because it means that my art has entered into a general and global sharing mechanism. I don’t believe in the myth of the individual artist. I am an artist because I want to contribute to the art world. As far as I am concerned, when you create these references in a spontaneous way it is a proof that I am working in the right way, recognising my work, but also its limits.

GG: I keep looking at your works and I am enraptured by the cuts you give to the scenes. They seem extremely photographic to me and reveal a lot about the study behind them and your visual culture.

AS: My paintings come from photos. Initially, I used photographs found on the web that struck me for their composition. Today, however, I mainly use photographs of people I know, and I feel a greater responsibility for the work. Generally speaking, I never use a single pictures, but I take several shots, recombining them together first in my head and then directly on the canvas, without the mediation of preparatory drawings or graphic proofs. I work directly with the brush, because in my work I also pay great attention to error. I look for the error, because this allows me to create escape mechanisms that help me to improve my research. In general, the photos I choose are those that refer to the poses normally found on Instagram or social network photos. My bodies allude to the visual culture of today’s society, they allude to Instagram because it is the biggest platform for displaying one’s body.

GG: It’s interesting that you start from digital photography, from Instagram, and then, through a process that we might describe as artification, you go back to the world of social media through an allusion to the clichés of photographic poses, but with the medium of painting.

AS: The pose, especially in social media, is set. You look for the best posture, but it often looks fake. Even in that case, the choice of a pose, the choice of a posture is linked to the attempt to enhance one’s body. My painting tries to highlight the falsification of social culture, but, above all, it draws attention to what in the common exception are the “flaws” of the human body. Emphasising cellulite, for example, is a way of enhancing it, of making it sensual. When we look at our image in the mirror, we do not like ourselves. On the other hand, in pictures we see the best version of ourselves. We need to feel filtered by another medium. Painting, then, is a way to reflect on this process to which we are all exposed. It happens sometimes that my painting, too, becomes a filter.

GG: Compared to the contemporary scene, how are the new generations of artists approaching this reality, which from a social, health and economic point of view always brings new challenges?

AS: The interesting thing I’ve noticed is that before the pandemic everyone tended to act in an individual and selfish way. The pandemic has erased any kind of certainty. The wonderful thing is that groups of artists are emerging, working in the same spaces, side by side. The competition stays high, but it is interesting to realise that we cannot act alone. In Venice, Milan, Rome, Turin and Naples, groups of artists are emerging. Many young artists have realised that selfishness does not suffice and that it is better to create a system, while maintaining their own personalities. Another important aspect is that people finally understood that art does not only mean artist, but it also means gallery owner, curator, collector, public, art dealers. Before, there was a super-ego, while now I see an awareness and sensitivity that seems to be more courageous than before. From a social point of view, artists are starting to speak out. Social media has become fundamental, and the pandemic has had a big impact. The need to constantly show has been fostered by Instagram, and it is not only the artist who uses social media to make their work known, but also gallery owners and curators, for example. Social media can be an amplifier of one’s work and I personally have a pro-social approach. Instagram has made me discover new artists or read articles I wasn’t aware of. It is important that there is a strong tool that, if well used, can offer you useful information. Obviously, it should be used discreetly and intelligently because the risk is to make works suitable for Instagram walls but not for the real life. The important thing is remembering that the real work is in the studio. I don’t paint for the gallery, I don’t paint for the money. I paint to give a trace of cultural heritage that future generations can develop. My time is limited, and my artistic research will not continue forever, but I can contribute, as older generations of artists have done. I hope that my work will also become a relay to be passed on to those who come after me.