Pier Paolo Pasolini’s painting on view in Rome to celebrate his 100th anniversary.

Words Gianmarco Gronchi

In a review of the volume in the I Meridiani series, devoted to Roberto Longhi, Pier Paolo Pasolini, recalling hat had been his professor of art history during his university days in Bologna, writes: “The course was the memorable one on the Fatti di Masolino e di Masaccio. Indeed, slides were projected on the screen, and the totals and details of the works, were coeval and executed in the same place, by Masolino and Masaccio. The cinema acted, albeit as a mere projection of photographs. And it acted in the sense that a “shot” representing a sample of the Masolino world – in that continuity which is precisely typical of cinema – was dramatically “opposed” to a “shot” representing in turn a sample of the Masaccio world.” It was there, in the classrooms of Via Zamboni in Bologna, during Roberto Longhi’s university courses, that that “figurative fulguration” took place that would later be decisive for Pasolini’s artistic and cultural lexicon. With these premises, it is easy to understand how figurative art and painting were a central passion throughout Pasolini’s life. On view until April 23, 2023 at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome, the exhibition Pasolini Pittore, therefore, aims to rediscover this relationship, concluding the celebrations for the centenary of the Friulian writer and director’s birth.

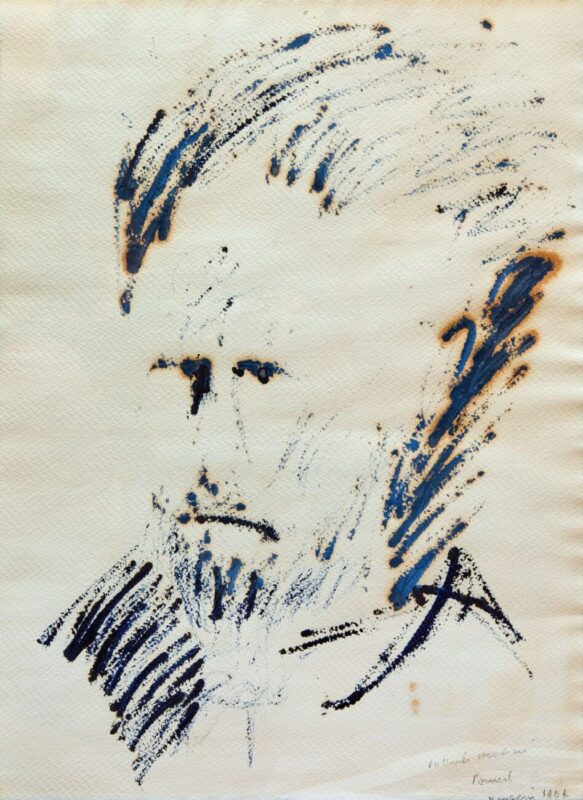

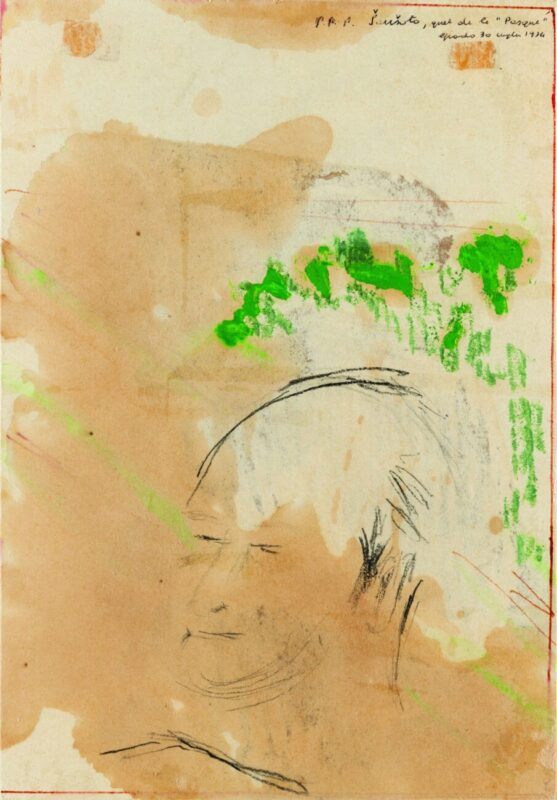

Curated by Silvana Cirillo, Claudio Crescentini, and Federica Pirani, the temporary exhibition presents a body of about 150 pictorial works, many of which were created by Pasolini himself, allowing visitors to retrace not only the life of the Friulian director and writer but also a segment of Italy’s twentieth-century cultural history. The exhibition opens with a homage to his native lands, almost an echo of the coeval poetic trials in dialect. Testifying to the young Pasolini’s early fascination with the practice of painting are still rural landscapes with an intimate flavor, which simultaneously investigate the origins and identity of his own family. These, in the words of Capitoline Superintendent Claudio Parisi Presicce, are “intense and vigorous works that make the visitor reflect on Pasolini’s artistic practice at a time when, as the artist himself states, he was above all painting and writing poetry, mostly in Friulian, which reinforces the visual and mental, conceptual and physiognomic comparisons and references between word and sign. It is a pictorial sign, Pasolini’s, lived in the wake of realism, as far as the subjects of his works are concerned, and expressionism as far as the use of graphic line and color is concerned.” Starting precisely from these early canvases made and still preserved in Casarsa, the exhibition winds through thematic spheres among which stand out the portraits of friends, and family members, but above all of the most prominent figures of Italian culture of the time. Defined as “portraits of the soul,” alongside the portraits of cousin Nico Naldini, his mother Susanna, and cousin Franca, we find a series linked to the protagonists of the literary and cinematographic world, including Andrea Zanzotto, Giovanna Bemporad, Laura Betti, and Ninetto Davoli. Among the portraits, those dedicated to Ezra Pound and Maria Callas, the Medea in the film of the same name directed by Pasolini in 1969, stand out for their expressive power. The portraits of Callas, in the words of Parisi Presicce, “highlight the cultural and linguistic mediation, in some respects sign-like, that the artist has always enacted. Pasolini, moreover, was always more interested in ‘composition’ – with its contours – rather than ‘matter,’ in line, therefore, with that pictorial phase of Italian art that precisely between the 1960s and 1970s was increasingly defining itself also for the civil commitment with which it was saturated.”

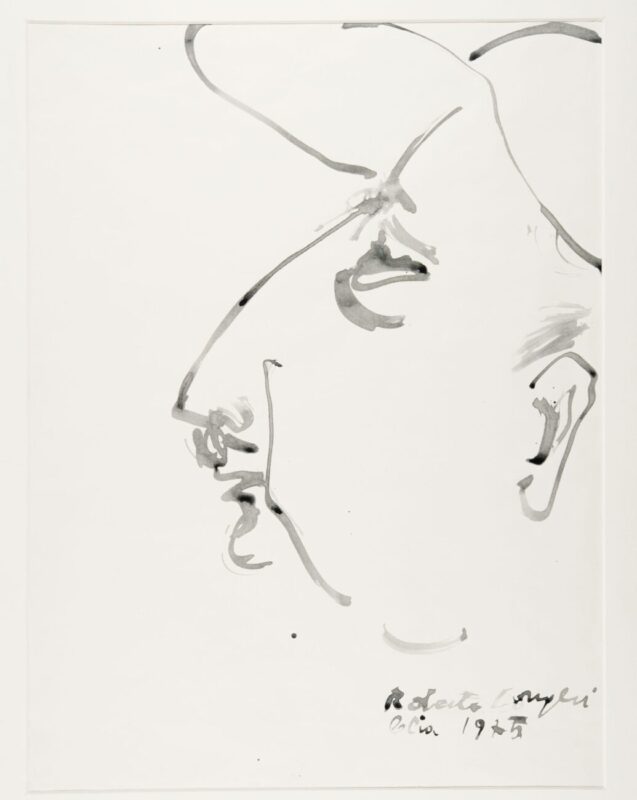

The exhibition also features works by well-known 20th-century artists, including Carlo Carrà, Filippo de Pisis, Giorgio Morandi, Mario Mafai, Scipione and Antonietta Raphäel, who were called upon to testify to Pasolini’s relationship with the coeval artistic and cultural scene. Also exhibited for the first time is a careful selection of works of art collected by the writer during his lifetime, presented here “with the intention of emphasizing how certain artistic and stylistic passions ran through Pasolini’s life and painting.” In a journey that starts from painting and returns to it, the exhibition does not fail to offer visitors portraits of Pasolini himself, executed at different times by names central to the Italian art scene of those years, including no shortage of Renato Guttuso, Carlo Levi, Milo Manara, and Mario Schifano.

An exhibition that intends to address the theme of Pasolini as a painter could not have been complete without the portraits-tributes to Roberto Longhi, the main cause of the Friulian author’s love for the figurative arts. Perhaps it is no coincidence that between 1974 and 1975, Pasolini, in voluntary retreat in the Torre di Chia, “in the most beautiful landscape in the world, where Ariosto / would have gone mad with joy,” devoted himself strongly to paint, returning with stubborn fidelity always to the same subject: the profile of Longhi printed on the boxed set of the volume I Meridiani Mondadori, freshly printed for the editorship of Gianfranco Contini. To Longhi Pasolini dedicated Mamma Roma in 1962. To Longhi, who died in 1970, Pasolini thought intensely a few months before his tragic end. In November 1975, when the writer’s body was found lifeless on the Lido di Ostia, the unfinished pages of Petrolio remained on the floors of the Torre di Chia, alongside dozens of drawings with his master’s profile. But compared to the photograph printed on the Mondadori box set, Pasolini portrays the art historian’s profile in a mirror-image manner. Yet another vindication of life against the grain.