Exclusive interview with Tonino Tognana, rally driver winner of an Italian championship and holder of the record for debut victories (10) with new cars, between swift memories and new projects

Words Silvia Motta

You have also experimented with new collaborations involving young international artists…

Yes, the first was Endless, the famous street artist who signed a limited edition of porcelain pieces with the symbols of his most famous icons, from Lizzy Vuitton to Chapel N.5, as well as having painted a huge nine-by-nine metre mural on the wall of our factory, with the irreverent image of Queen Elizabeth making faces. What you see now, however, is the Ethnics series, which features a collection of “refreshing” vases, coffee cups and mugs, reinterpreted by the young designer Gianpiero Mastro: the spectacular hand-painting that characterises each piece depicts a different mask from ancient tribal cultures of different countries, and symbolises the connection between human beings and the divine.

Have they helped you in scouting them?

We are also followed by Cris Contini, who has art galleries in Venice, Cortina, London. We met, and he was immediately enthusiastic about the idea of creating limited editions of porcelain, thus our collaboration was born. Today, it is also fun.

Could you create limited editions of cars? My dream would be to invent a car that is perfectly and integrally customizable, totally personalized; like an ovoid bodywork, or rocket-shaped, gull-wing doors, ball-shaped headlights, or designed by an artist, indeed…

An unattainable example is the Isotta Fraschini, one of the myths of the automotive world: it was produced only in the form of a chassis, it was not bodyworked and therefore was passed on to the most prestigious and established body shops, including Farina, Sala, and Castagna, which were very fashionable. The latter was a Milanese body shop, where only grand luxury cars were made. The Isotta Fraschini was dressed with the most beautiful and elegant bodyworks, the dimensions were monumental, the interiors were sophisticated salons rich in crystals, silvers, and burls, with precious damask upholstery. The “Società Milanese d’Automobili Isotta Fraschini” was established in Milan in 1900 by a group of passionate and wealthy gentlemen and soon became the most prestigious Italian luxury car factory.

So it could be a reality even today…

No, it wouldn’t be possible with today’s electronics related to the functioning of cars, and especially now there is the requirement of homologation.

However, for some luxury cars, there is the possibility of customizing the bodywork extremely, in colour and designs, and even the interiors, you can choose upholstery of very refined leathers or fabrics, or precious details, gold, diamonds, and hyper- technological equipment… for a certain level of clientele, extreme customization is essential.

Absolutely. If we think only of the boundless pool of buyers in the USA and the Middle East, between Dubai, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, there they ask especially for that type of cars. If they spend money, it’s better that they spend it having fun, and creating wealth for others, who work for them.

We’ve arrived in the center of Treviso, at Alfredo’s…

It’s a restaurant since 1961, which is also a historic gem, decorated in the Liberty style. It immediately appealed to the city’s elite, and over the years, it has charmed many well-known faces. The reason I come here is because I too am in love with this place. And they have all our porcelain, which makes everything even more precious.

When did you come up with the idea to become a rally driver?

I started driving very early, at 8 years old! And as soon as I could, I got my license and began racing.

Was there someone in your family who shared your passion for engines?

My dad had a passion for cycling and sponsored an amateur cycling team, called Tognana Pinarello, when I was just a kid. Pinarello, also from Treviso, was the most famous bicycle manufacturer in Italy along with Colnago. My dad stopped financing the team when he realized that the sports director was doping the boys, and even though doping was once a normal thing, he did not want to be complicit. So, as a kid, I raced on bicycles too before realizing that it was less tiring to go on a motorbike, and even less so with a Ferrari… that’s how the passion for four wheels came about…

How did you live your golden youth as a handsome provincial boy?

At 8, I learned to drive from a Venetian lawyer, a family friend, who came to us every weekend. I drove around my dad’s factory because the yards were empty on Saturdays and Sundays. I remember I couldn’t even reach the clutch! And he always followed me, changing the car year after year, just to let me drive the right one. Not only that, but also because he liked beautiful cars. But the fact that I learned to drive from an islander Venetian wasn’t a good story to tell… However, at 16, I bought an Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint 16 without plates from a scrapyard, and we went racing with friends on country roads because no one had a license. We raced until we broke it, obviously, driving through potholes, then we bought a very ugly Volkswagen 1005, all without our parents knowing who actually pretended not to know.

Tell me about the transition from amateur youth racing to road racing.

To challenge each other among friends, we needed a circuit where we could time ourselves… There’s a military field here 15 km away, in Maserada sul Piave, called “Parabae,” a vast expanse of dirt roads where the military trained, even with tanks. To get there, you had to cross the city and I didn’t have a license, and the car had no plates, no tax, and no insurance. The only one with a license was our friend with a R4 Renault, so we invented that he would tow me on the Alfa Romeo with a big sign on the back, which read “car in tow”. I disguised myself with a hat on my head and a pair of big glasses, to not betray my age. Finally, I reached maturity and then it was customary to be gifted a car as a reward for promotion and the end of high school. I graduated at 18 with top grades, and so I found the car wrapped up under my house.

And what was your first car?

Thanks to my academic achievements, I demanded the one I wished for. But not the one all the boys wanted, the 128 FIAT Coupè, or the ultimate, which was the Fulvia HF. Since the Opel Ascona, a very robust German car, ran and won in rallies, I asked my father for it and he couldn’t understand why. He said it was the car of German butchers: he saw them in Jesolo in the summer with those green or yellow cars. When I managed to convince him, after a month he understood.

So you started racing your rallies as soon as you got your license…

You needed a year of having a license to get the sports license to race. I cheated and raced two months before the year was up. Also because I had been driving for over 10 years.

But you’re a criminal! What was your first rally race? And how did you place?

I’d rather say an iconoclast, it’s not that I would have driven better two months later… The first was the Rally di Cesena in April 1975, I would have turned years old a month later. I finished 52nd, which was good, because the car was not prepared, it was all standard. But in the special downhill stages, where the engine didn’t count, I remember making the best time in my category. After 2 years I was already an official Opel driver.

Choosing the Opel Ascona was a shrewd move, since the Agnelli family would have never immediately taken you on as an official driver for Fiat. They did later, and so did Ferrari.

I raced in ‘77/’78/’79 with Opel, winning the Opel Italy championship. Indeed, the year after, Fiat, through the Jolly Club of Milan, signed me up and I raced with the official 131 Abarth. It was ‘80, and I was 25 years old.

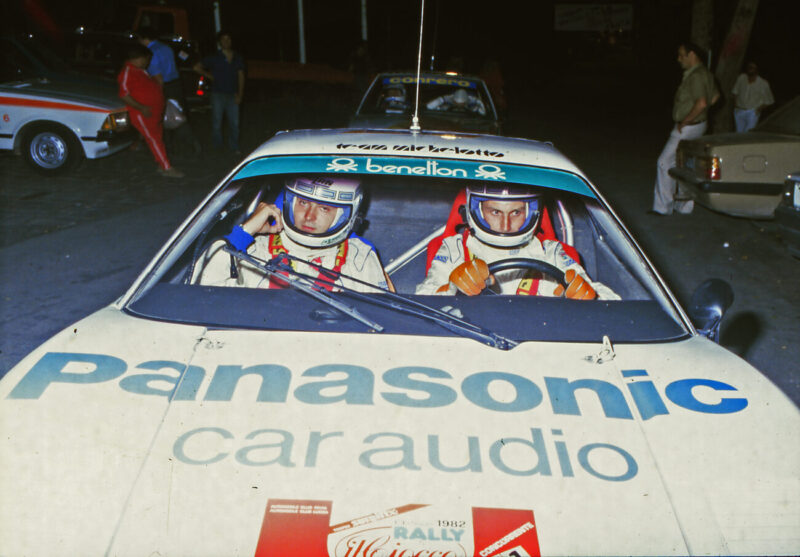

Who was your co-driver?

An Italian-American guy, Sergio Cresto, a legend, who died very young in a tragic race accident at the Tour de Corse. The morning before he passed away, with a grim premonition, he wrote a letter expressing his last wishes, thanking me for the years he raced with me. It was 3 and a half years with Sergio; he first raced against me with another Opel driver. With a co-driver, you must have blind trust, as he does in the driver. A kind of symbiosis always develops with the co-driver; you live together in the car all day long. In my career, I’ve raced 135 rallies, won 22, and I’ve had very few co-drivers, maybe a dozen at most, with some I’ve only raced a couple of times.

Did you ever race in Formula 1?

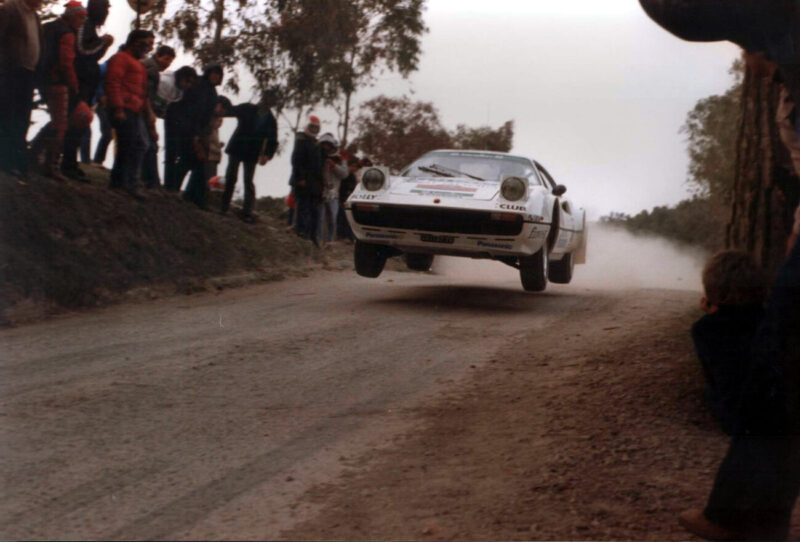

No, always in rallies, I then started racing with Ferrari in ‘82. That year was the only time in history that Ferrari won an international rally championship against the Lancias, Audis, Opels, Porsches… Back then, engineer Enzo Ferrari was still alive – he died in ‘88 – and so I had the chance to meet him. Indeed, he also cared about road racing, I’ve been to him 7-8 times. He always hid behind large dark glasses, to not let the interlocutor know what he was thinking: he was a great character. Very tough.

Could you tell if he liked you or not?

In 1982 I debuted in the Targa Florio, the 10th International Rally of Sicily, my first race with a Ferrari 308 GTB, and I won it. The Engineer sent me a telegram that same afternoon, which I still keep today, that read: “Hearty congratulations on your victorious debut.” It was the eleventh time that a Ferrari had won the Targa Florio, which is the oldest race in the world, dating back to 1900. Back then it was a speed race, 57 km on the Madonie circuit run 11 times, only it was on the road, with climbs and descents, instead of on track. As a driver, I have an unbeaten, and I believe unbeatable record: 10 absolute victories with 10 different cars on debut, that is, the first time driving the car.

It means that it’s the driver who is good, like a sculptor with a chisel in hand. From a shapeless mass, a masterpiece can emerge, the same with a car.

I’m proud of this. Indeed, the beauty is that I won the Targa Florio with the Ferrari ahead of the other Ferrari of Jean-Claude Andruet, the French champion who had won the year before, older than me by 12 years, and who could test the route with the mule car while I with a rental car from Avis or Herz… because we certainly couldn’t have another Ferrari! Returning to Enzo Ferrari, let me tell you an anecdote. I had won the Ciocco rally, it was June and the Drake immediately summoned me to Maranello because he wanted to know how the race went. At 9:30 pm we were still in his office talking, me, Michelotto who was the racing car preparer, and Engineer Ferrari, always sitting with his dark glasses behind the desk. There was a window overlooking the entrance hall where all the workers passed in and out of the plant. At one point I see him get up suddenly, go to the window and see them leaving, it was a summer evening and there was still a lot of light. Then he starts shouting, and Valerio, his secretary, comes running: “Engineer, what’s happening?” He answers: “Valerio, where are they going?” And Valerio says: “Engineer, at 9 pm they’ve finished their shift, they’re going home.” “Valerio, go out immediately, tell them to return to work while there’s still light outside! Understood? Or should I send them to Iceland…” He was one of those father figures who ultimately get everything.The workers went back to work.

What about your refusal to Enzo Ferrari…

Back in 1982, after winning the Piancavallo rally in September, I was leading the Italian championship with only two or three races left. I was a contender to win it, and it was a three-way battle: me, Miki Biasion, who later became a two-time world champion, though I gave him his first win, and Fabrizio Tabaton. I was interviewed by Autosprint, the most important magazine of the time, and they published a double-page headline piece: “I win and I retire.” One should never say such things, especially when I hadn’t even turned 27. Autosprint was released on Mondays in Bologna, and it took at least a day to reach Treviso since there was no internet back then, only word of mouth. On Monday afternoon, Valerio, Ferrari’s secretary, called me: “Tomorrow morning the Engineer wants to see you in his office immediately.” I left on Tuesday morning without having read the article, caught between anxiety and curiosity. You should know that Engineer Ferrari had the habit of reading all the newspapers, cutting out articles, and making folders; there wasn’t a press review yet, he did it himself. I found Autosprint open on his desk with the title “I win and I retire.” Ferrari said to me: “Mr. Tognana, I’ve read the article, why don’t you want to race anymore?” I replied: “Engineer, look, I never imagined becoming a professional driver because I have an elderly father (my father was only 62 at the time, but he seemed very old to me) and four sisters. I’m the only son and I always thought I would have to follow my father in the family business.” And he said: “Mr. Tognana, if I had followed my mother’s advice, I would probably have been a good banker. But I would never have been Enzo Ferrari. Now please leave.” He thought he was the king of the world: he was over 80 years old, and for him, the fact that I, as a young man, did not feel blessed by Ferrari, was an offense.

Couldn’t you have combined your racing activity with the family business? You weren’t an employee…

I was part of the official Jolly Club team in Milan, I was paid to race, it wasn’t a hobbyist activity. Soon after, the Rally of Sanremo took place, also valid for the World Drivers’ Championship: on the tarmac, the Ferrari occupied the top position in the overall ranking, even winning the stage. The Drake enjoyed the fact that we with Ferrari were beating the Lancias, their competitors at Fiat… He continued to write to me, to send me his books, Christmas wishes, and a special and unique tie. Maybe he always kept me in his heart, but he didn’t take it well. So, I was practically winning the Italian championship with Ferrari, beating even all the official Lancia drivers of that time who raced with Alen, Vudafieri, Bettega, Zanussi, Tabaton. Moreover, the brand-new Lancia 037, which had been developed as the heir to the Stratos, had not yet won a race because they all finished behind me. Thus, when there were two races left in the championship, Cesare Fiorio, the Lancia sports director, thought it wise to force Angiolini, the boss of the Jolly Club, to sell my Ferrari and remove me from the 308, to put me on the Lancia 037 he would give me as the official team. When he found out, the Engineer immediately called me in Maranello, and said: “Don’t Ferrari 125 S, Venice 2011, boarding on a barge. worry, I’ll give you another Ferrari, Andruet’s is already ready for France, you will race with my car.” I went home, happy that Enzo Ferrari cared so much for me. Two days later, the Engineer receives a call from Turin, and Valerio phones me: “Look, the Engineer is sorry, he says you must race with what the Team provides, and that contracts must be respected.” Clearly, the order had come from Fiat: Ferrari didn’t need rallies to sell cars, but Lancia did, as an effective marketing tool. I was so angry that I got in the car that they hadn’t let me test until the evening before the race, and I won it, immediately, and then the Italian championship. It was the first victory in the history of the Lancia Rally 037, so I ended up on all the front pages of the newspapers, not just the sports ones. What does the engineer do then? The day after all the newspapers came out, which he had cut out the full-page advertisements from that read: “Tonino Tognana on Lancia Rally wins the Italian international rallies championship,” he recalls to Maranello the Lancia racing department engineers, to whom he provided Ferrari engines for the Lancia LC1 track competition, and tells them: “Since you don’t need the Ferrari to win in rallies, then you will no longer need the Ferrari engine to race on the track either.” Everyone was silent and terrified for at least 5 minutes, thinking about how they could then continue to race in the circuits for the world Manufacturer’s championship without the Ferrari engine anymore. Then he continues: “Indeed, I respect contracts, but from tomorrow the engine will leave Maranello completely disassembled into pieces, and you will assemble it yourselves in Turin.” Indeed, Lancia won the championships with the Ferrari engine, just as Ferrari had been the engine of the Stratos.

After all, the rally world told a noir novel, full of twists and backstage…

It’s a very competitive world, more fascinating then. My feeling is that today’s rally world has deflated, at least here in Italy. Back then, there were five official manufacturers racing with their hired professional drivers, hundreds and hundreds of amateur drivers, and hundreds of thousands of spectators on the roads. The Fiat-Lancia group hasn’t made any rally cars after the Delta, and the Japanese began to win. So, in Italy, the less talked about it, the better. Moreover, after the severe accident in ‘86, in the Corsica rally, where Henri Toivonen and “my” navigator Sergio Cresto lost their lives, a fierce campaign against racing was mounted. Then followed other tragic deaths of champions, then added was the absurd controversy against unsustainable pollution.

But you, Tonino, never really stopped racing…

The most beautiful thing is that after many years, in 2007, at 52 years old, Porsche, the official German team, called me and proposed to do the Transiberian aboard a Cayenne S, which had just launched, 7700 km from the Red Square, to Ulan Bator, Mongolia, all off-road. And I finished

Here in Treviso, how are you considered? Are you a Treviso glory?

My ancestors arrived in Treviso in the 1700s from Switzerland and Austria, and almost all the descendants never wanted to leave the city. The Tognana family here is loved, started with the brick kilns since 1770, and carries on the territory a business success created by my father, who founded the porcelain company in 1946, and passed away in 2020 at 100 years old. My father was always a very curious man and somehow multifaceted: a passionate traveler – he traveled around the world in 80 days, like in the book by Jules Verne –, interested in various cultures, always open to human contact, not at all conditioned by social status or rank, eagerly sought nourishment through study and culture. His interests ranged from politics to sports, from economics to literature, so over the years he has built a library that now counts thousands of volumes.

What unites this past of yours, which is also present because it is part of your DNA as a challenging and winning champion, with the activity you are carrying forward? You have resurrected a porcelain manufactory founded over two centuries ago by one of the master ceramists of Venetian baroque…

Today, with Geminiano Cozzi Venezia 1765 is a beautiful challenge. My father already encouraged me to challenges, I keep a letter from him, which he wrote to me in ‘78, when I was at the beginning and was about to become an official Opel driver. As a father, he was strict and demanding, but at the same time liberal and generous, he always indulged all our children’s passions, like motorsport in my case.

How was your entry into the company?

I joined my father from when I wore shorts. I accompanied him to international fairs, and I worked in the warehouse during holidays and summer vacations. When I came home from the rallies, no matter what, I went to the company. I always felt the call of the family, but at the same time, I wanted to experiment. At 21, I graduated in Economics and Commerce, at Cà Foscari in Venice, I finished early because I didn’t want to be accused of neglecting my studies for racing. My father gave me my first car, but then I found the sponsors myself. After a year and a half, I was already an official driver and earned enough to buy the apartment where I later lived with the race prizes. But there was always someone who said: look, it’s not your job, I had four sisters born before me, I was the youngest, and the only male. No one ever pressured me, but it was implicit that I should join the company.

Now you have a new toy, the Isotta Fraschini. When did this infatuation start?

It’s a toy that is getting great results. The passion for racing is still very much alive today. I shared this with Giuliano Michelotto and a group of very valuable former colleagues, friends, and professionals, giving life to the project of resurrecting the legendary Isotta Fraschini brand, whose story began in Milan on January 27, 1900. Since then, it has become a symbol of technology, innovation, elegance, and luxury. In the racing world, Isotta Fraschini has written unforgettable pages. Its iconic models dominated important automotive competitions, winning the Targa Florio and the Coppa Florio in 1907 and 1908, and the prestigious Tipo IM shone at Indianapolis in 1913 and 1914, driven also in 1920 by a young Enzo Ferrari. The Tipo 8, with its variants, became a symbol in the ‘20s and ‘30s, owned by monarchs, politicians, cinema stars, and members of the high bourgeoisie. So, we chose to bring back to new glories a jewel of Italian automobilism. The racing models of the powerful Isotta Fraschini Tipo 6 LMH Pista have been practically all sold. The Isotta Fraschini Tipo 6 LMH Strada, on the other hand, is presented as a direct evolution of its competition counterpart, which will debut this year in the World Endurance Championship. This exclusive gem, reserved for only 12 lucky buyers, retains all the characteristics of its racing version but has been slightly tempered in responses, the external line, and ground clearance. However, it maintains a behavior that ensures a uniqueness unparalleled in the panorama of the most extreme hypercars worldwide. And it’s a hybrid car, because it has a thermal engine with 750 horsepower at the rear, while at the front wheels, it mounts an electric motor that recharges on braking, so that when you exceed 150 km/h in a curve and the additional 270 horsepower of the electric motor kicks in, it becomes four-wheel drive. These are technologically very advanced machines, created in Padua by Michelotto Engineering, with a team of 100 people working on it. Besides these two authentic jewels, Isotta Fraschini is ready to bring its third engineering marvel – the Tipo 6 Competizione – onto the most important stages: the World Endurance Championship and the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 2024. A triumphant return to the stage for the historic Milanese company. And how could it not be?